|

|

About Continuum Advertising Advisory Committee Archives Contact Us Continuum Home Faculty/Staff Subscribe related websites Alumni Association Marketing & Communications University of Utah Home |

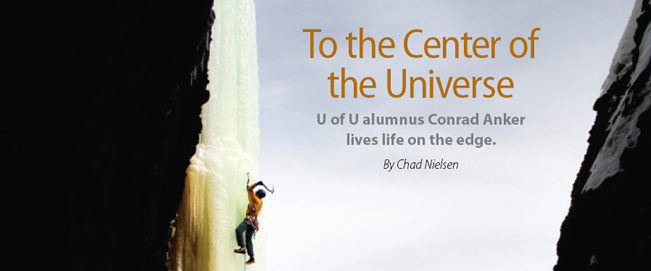

ALUM PROFILE Anker climbs the "Dancing with Hippos" ice pillar on Barronette Peak at the northeast corner of Yellowstone National Park. The day before the monsoon buried India’s Himalayas in snow, Conrad Anker BA’88 stood at the rocky edge of Tapovan meadow, reciting the Hindu names of the surrounding mountains. “Mount Shivling,” the lanky American said, pointing to the nearest snowcapped pyramid, “is the abode of Lord Shiva.” His disheveled blond hair flailed against the gusting wind as his blue eyes focused farther on, where a massive wall knifed skyward like an upturned spade. “Meru is the peak we’re here to climb. Meru is the center of the universe,” said Anker, alluding to Hindu mythology. Anker has devoted more than 20 years of his life to climbing the world’s summits, making his home away from home among clusters of tents like Tapovan Base Camp. His three-man team spent four days there this fall, blogging, reweighing their 10-day rations, and acclimating to the altitude. Anker, perhaps the world’s strongest big-wall climber, kept one eye on Meru. His previous attempt to climb the Shark’s Fin, a 4,265-foot pillar at Meru’s northeast corner, had been doomed by snow, so this time he logged the weather in his personal notebook. “Every morning, there’s this six-hour window where it’s clear,” he said. “We can climb in that, and sit out the storms that come in every afternoon—working within what nature is.” The team started this year’s climb on September 16. When snow began falling the next day, the three mountaineers calmly anchored an artificial ledge against the stone wall and climbed into their tent to let the bad weather pass. But the snow didn’t stop. By nightfall, Meru was buried under six feet of powder. When the white flakes were still falling the next morning—and the next, and the next, and the next—Anker remembered a hard lesson: nature always has the final say.

Conrad Anker

Born in 1962, young Conrad started climbing as soon as he could walk, when his father took him to the top of 13,057-foot Mount Dana, near their home in Big Oak Flat, Calif. That hike became a family tradition, like the annual two-week backpacking trek into the Sierra Nevada wilderness. “We grew up in the high country,” says Anker, who has two older sisters and a younger brother. Yosemite National Park, just 25 miles away, was their playground. Anker didn’t rock climb until he was 18, but he relished communing with nature—hearing a bird sing, watching a chipmunk jump from limb to limb, or foraging for huckleberries like a black bear. After high school, Anker moved to Park City, Utah. To paraphrase a T-shirt slogan from that era, he didn’t let school get in the way of his mountain education. He took jobs that left him plenty of free time to ski and climb—like flipping burgers at Park West (now The Canyons), where he slept in a tent near the slopes. In 1983, he decided to enroll at the University of Utah, majoring in commercial recreation. “The U had what I was looking for, which was a good education in a scenic place,” he says. “We’d do Westwater. We’d go climbing in Zion National Park, or down into Canyonlands, the Towers. We did a couple trips to Alaska. It was branching out and taking the skills you can learn locally and using those for a springboard later in bigger trips.” Climbing also fueled Anker’s social life. He worked at Campus Recreation and the North Face retail store, and shared an apartment with Mugs Stump, a legendary climber (and former Penn State football player) who became his mentor, friend, and climbing partner. In the canyons along the Wasatch Front, he made many friends across the social strata, from mountain-climbing bums to former Salt Lake City Mayor Ted Wilson BS’64. “You could never be with a safer climber, or a guy who was more dedicated to enjoying the climb for its more human elements,” Wilson says. “He always saw the joy of it. He always made mountains more than they were. He worships the earth, in a way.” Professionally, Anker became something of a missionary for that religion. By 1992, after scraping to pay for multiple first ascents—from a new route on Streaked Wall in Zion to Alaska’s Gurney Peak and the Kalidaha Spire in India’s Himalayas—Anker became a founding member of the North Face Climbing Team, as well as a full-time employee with health insurance and a 401(k). As a marketing vehicle, his association with North Face paid for résumé-building climbs from Baffin Island in the Canadian Arctic Archipelago to Patagonia, Antarctica, and Pakistan. He documented his exploits in print, film, and slide-show presentations. “You have this chance to see [nature] in a different way and share it with people,” he says, “for people to see that it’s not that scary. They can go out and have a wilderness experience on their own.” But nature is not always kind. On October 5, 1999, Anker hiked across a glacier at the base of Shishapangma, a 26,291-foot peak in Tibet. Along with best friend Alex Lowe and cameraman Dave Bridges, he was scouting routes to the summit; they intended to ski down. Suddenly, a crack echoed overhead; 6,000 feet up the mountain, a massive slab of snow and ice had cut loose, sending an avalanche toward them at impossible speed. The trio scattered. Anker was caught in the snow, dragged 70 feet and partially buried. He emerged to a silent, pristine white landscape. He searched, called his friends’ names, checked his watch. The minutes ticked by, leaving only questions. Death is an everyday risk for mountain climbers. Anker had already lost Stump, who fell into a crevasse while descending from the summit of Alaska’s Mount Denali in 1992. And five months before the avalanche, Anker had faced mortality on a grander scale, when he found the body of legendary mountaineer George Mallory, who, during an attempt to be the first person to reach the summit of Mount Everest in 1924, disappeared in heavy weather. Anker’s historic discovery sent ripples through the mountaineering world and earned him a moment of mainstream fame. And the same slope, revealed by that year’s unusually light snowfall, was also strewn with the frozen remains of more recently deceased climbers. Even Anker had once fallen nearly 80 feet onto his back (glacial snow cushioned his impact, but today the moderate injury still bothers him on occasion). But Lowe’s and Bridges’ deaths changed something. “We knew the risk,” Anker wrote in a tribute to his companions for the February 2000 issue of Climbing magazine. “Are the risks worth the rewards they bring?” His essay frames an eloquent argument for the intrinsic value of climbing, exploration, and risk. But on a personal level, Anker’s conclusion was clear: “When I ask myself if this tragedy is worth the reward climbing brings, I answer, ‘No.’” Anker’s North Face bio shows a rare blank of first ascents that year. Back home, Anker traveled to Bozeman, Mont., to comfort Lowe’s widow, Jenni. Both ended up finding much more. As he and Jenni grew closer together, Anker struggled with new doubts about climbing. Was it worth the risk? Could he put Jenni through that again? What about Max, Sam, and Isaac, the sons Lowe left behind? “Do I walk away from it?” he now recalls asking himself, looking back. “Would it change who I am as a person?” The survivors married in 2001, and Anker adopted the boys. In spite of his doubts, by that time he had ascended the east face of Vinson Massif in Antarctica. “I wouldn’t be myself if I had quit climbing,” he says.

The monsoon rages into the eighth night. The insignificant little tent clings to the wall, a nylon parasite on the impassive face of Meru. Inside, the three mountaineers remain trapped on their artificial ledge. They don’t know how long the snow will continue, so they eat just enough to fend off the cold. There is plenty of time to think. Random images float around in Anker’s mind. Some surface. The red stone of the Streaked Wall at Zion, where he opened a route with Stump. The alabaster skin stretched across Mallory’s frozen back. Lowe’s boyish grin. Jenni watching anxiously out the front window. They all knew what they were choosing. “Life involves risk and pain and suffering and hardship,” Anker commented from his home office just before the trip. “We try to put that away and say life isn’t that. Life is soft and easy for us. We make that the center of the American existence—that our lifestyle cannot be taken away from us. Mass consumption: ‘I want it now and I want it to the degree I want it. Taking that away would be taking away my freedoms.’ We’ve taken the concept from free speech and applied it to consumerism: ‘You can’t take away my big car.’ I question that.” Anker has long seen climbing as a way to effect change. He sits on the board of the Conservation Alliance, founded the Alex Lowe Foundation’s climbing school for Nepali guides, and encourages outdoor recreation on the speaking circuit. But in Anker’s form of spirituality—inspired by Buddhism, but molded by his own experience—climbing is intrinsically valuable to humanity writ large. “I represent exploration, our risk-taking genes, our problem-solving genes,” he said. “Those ideas made humans the dominant species on this planet. It’s what put us on the moon. It allowed us to explore quantum physics. It’s this need to explore—climbing the mountain and looking over the next ridge.” But sometimes, the next ridge stays out of reach. On September 25, Anker unzips the tent door and grins through cracked lips. The sky is clear. The three climbers assess their dire status—and, of course, decide to press on, inching their way toward the summit. They climb through every break in the weather. Their bellies ache with hunger. Their fingertips are frozen. Nine days later, facing a complicated series of overhangs, the team turns back, just 300 feet short of the summit. “We were strung out,” Anker says. “We were hurting. I lost 15 pounds. I’m a skinny guy to begin with.” The following week, 7,000 miles from the center of the universe, in Bozeman, Anker putters around his kitchen. He slices tomatoes, prods a pile of sweet Italian sausage bubbling on the stove, and boils a pot of rigatoni. This is a regular Sunday dinner at the Lowe-Anker home, with a few guests. He sips some red wine reduction sauce from a wooden spoon, just a taste. He still doesn’t know if he’ll take another stab at Meru, but dinner will be phenomenal. —Chad Nielsen is a Salt Lake City-based freelance writer. |

|

More About Conrad Anker There’s no shortage of additional information about Conrad Anker available online. Some highlights include: |