Vol. 15 No. 3 |

Winter 2005-06 |

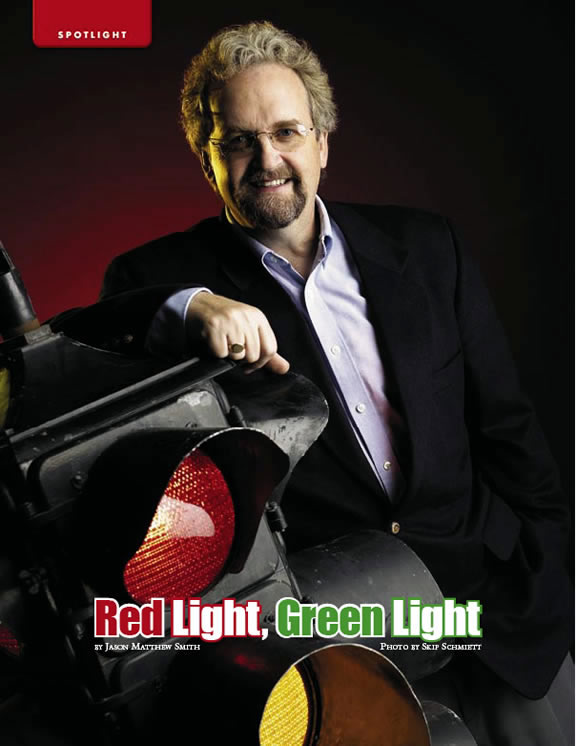

Social gatherings are sometimes uncomfortable for Professor Peter Martin, director of the U’s Utah Traffic Laboratory (UTL). Maybe he’s just headed across the room to get a drink, when soon enough word has spread that Martin works with traffic. That is, his specialty is coming up with ways to move people—either in cars or by mass transit—from point A to point B with as little delay and aggravation as possible. Inevitably, halfway to the refreshments, Martin finds himself toe-to-toe with someone grousing about a traffic light on 4th South that seems to be calibrated for an intersection in Barrow, Alaska, not downtown Salt Lake City. That’s why Martin has taken to telling people he’s a gynecologist.

“No one asks questions then,” he says.

It’s not that Martin is ashamed of what he does. Quite the contrary.

Martin started out as a civil engineer, a concrete and calculations guy. He was raised and educated in the United Kingdom, earning B.S. and M.S. degrees in engineering from the University of Wales, and a doctorate in Real-Time Transportation Modeling from the University of Nottingham. After coming to the U in 1994 to direct the Traffic Laboratory, he has advised traffic engineers in countries all over the world, including India and China. He consistently found himself drawn to what could be termed the “warmer side” of transportation—such as dealing with transportation officials and politicians to fix gridlock snafus that affect the everyday commuter—rather than crunching numbers for contractors and designers.

He is, in essence, the human face for traffic in the Salt Lake valley, a liaison between theory and practice. He’s equally adept at schmoozing city and state bureaucrats with his Black Adder-meets-Alan Alda charm as he is analyzing highway fatality numbers or the quantity of “sneakers” (vehicles that turn at an amber light) at an intersection. And he’s keenly aware that the work he does happens largely behind the scenes.

“Transportation sits in the background,” he says. “But if you ignore it, you’re in trouble.” Someone has to take the pulse of Utah traffic and pass that data on to the right people. Martin and the UTL take measurements of things like speed variations between fast and slow drivers or the number of drivers illegally utilizing the carpool lane, and come up with conclusions and recommendations for transportation agencies. That information can validate or refute what engineers and planners were thinking, and can make or break project funding.

Through a bank of television screens in its lab in the basement

of the Kennecott Building, the UTL keeps an omniscient eye on the

ebb and flow of traffic in the Salt Lake valley. Martin and his team

of researchers, including graduate students, have unprecedented access

to the Utah Department of Transportation’s camera network, and are

able to monitor traffic volume, speed, acceleration, deceleration, or

what are innocuously termed “incidents” (wrecks, breakdowns)

from this location. They collate and pore over data for projects ranging

from the grandiose—analyzing information for the massive I-15 reconstruction

and realignment project just prior to the 2002 Olympic Winter Games—to

the more mundane, such as conducting studies of traffic signal timing

for snowy conditions.

The thing with traffic research, Martin points out, is that everybody’s

an expert, which he finds highly amusing. You’ve got a driver’s

license and suddenly you know the best way to time the traffic signals

between Salt Lake and South Jordan. You’ve got theories, and you’re

one of those people who accosts Martin at dinner parties.

But researching traffic is far more complex than people might think.

There’s a fair amount of prognostication involved as well. Martin must think five, 10 years or more down the line for his research. It’s all about the planning as he helps transportation agencies across the Mountain West picture what their highways and byways will look like in a decade or two. And he says the U is the best full-scale, real-time laboratory for what goes on in Salt Lake City. “On this campus, you’ve got a microcosm of the region,” he says. What’s happened at the U in recent years fairly typifies the challenges faced by transportation planners from Missoula to Monticello: explosive growth marked by single-car drivers, all looking for a place to park. Yet he points to the success of the TRAX light rail system as the U’s—and by extension, the Salt Lake valley’s—saving grace. “Had we not implemented light rail on campus,” he says, “traffic pressures would’ve been intolerable.”

Complicating his job, too, is the driver’s natural distaste for novelty and variation during the morning commute. “Generally speaking, with traffic control devices, change is not a good thing,” he says. He knows that drivers don’t like to be confronted with anything different—no orange barrels popping up, no signals operating in a manner markedly different from that of yesterday. Drivers want binary decisions: A or B. No choice C to muck things up. Routine. The work is more than just numbers, charts, percentages—he must take into account a healthy swath of psychology and human nature. He can look ahead, note trouble spots, and see danger coming. Martin understands perfectly well the curious interplay between people and their machines, and the roadways they use.

So at night, when he hears his young sons—not quite old enough to drive, but getting there—in their beds talking about getting one of those motorized scooters to zip up and down the neighborhood, he’s already preparing the rebuttal. He’s not the kind of father who warns, “Those are dangerous,” and leaves it at that. Instead, he says, “I’ve seen the data: Injuries sustained from those scooters are horrific,” and the boys know that they’ve lost this one. Better to hit dad up for a nice, safe Volvo and plenty of driving instruction when they turn 16. And, of course, to refrain from complaints about stoplights.

—Jason Matthew Smith is editor of Continuum.