Vol. 14 No. 3 |

Winter 2004-05 |

Diseases that we read about in the newspapers—such as typhoid, avian flu, SARS (Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome) and dengue fever—now have greater meaning for a handful of University of Utah students.

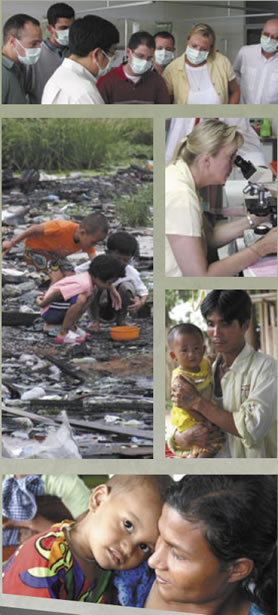

This past summer, the Utah Physician Assistant Program (UPAP) and the Public Health Program offered an immersion course in international medicine in Thailand. Through visits to city slums, refugee clinics, modern hospitals and labs, traditional medicine clinics, and a Buddhist hospice, students and faculty got a close-up look at how a small country with limited resources deals with its complex public health issues.

Summarizing the value of the experience, UPAP faculty member Dan Crouse MPS’04 says, "The reason a trip like this is important for our students is that most public health problems are born of poverty. The poverty in Thailand is many times worse than here. Then you throw in tropical diseases and there is a lot to see, a lot to learn."

The three major diseases worldwide are HIV, malaria and tuberculosis. In Thailand the students saw these diseases in addition to others they have only studied, such as leprosy, SARS and dengue fever. They spent two weeks performing concentrated coursework in and around Bangkok, doing fieldwork in slums, visiting clinics in rural settings and touring insectology labs, all with the help of translators.

UPAP program director Donald M. Pedersen PhD’88 knew it would be a life-changing experience for the students. "Some of our graduates take this knowledge into the Peace Corps, some work overseas for American companies, and others fi nd work in underserved populations in the United States," he says. "They will all be much more knowledgeable about diseases rarely seen here, and they will also be more sensitive to international patients as a result of their Thailand experience."

Physician

assistant student David Laisy was impressed by the resilience of many

of the people the group encountered. He recalls a trip through a slum

district in Bangkok, noting: "People were living in 8-foot-by-8-foot

run-down shacks made out of bits of leftover wood, with all of their worldly

possessions piled around them. Many are forced to sleep on the floors

because they cannot afford, nor do they have room for, a mattress. Dirty

clothes, cramped living conditions and living day by day. Yet despite

these hard living conditions, we saw families that would smile and wave

as you walked by, dads playing with their children, and children laughing.

We did not feel in any danger during this visit but in fact felt and saw

a strong sense of community."

Physician

assistant student David Laisy was impressed by the resilience of many

of the people the group encountered. He recalls a trip through a slum

district in Bangkok, noting: "People were living in 8-foot-by-8-foot

run-down shacks made out of bits of leftover wood, with all of their worldly

possessions piled around them. Many are forced to sleep on the floors

because they cannot afford, nor do they have room for, a mattress. Dirty

clothes, cramped living conditions and living day by day. Yet despite

these hard living conditions, we saw families that would smile and wave

as you walked by, dads playing with their children, and children laughing.

We did not feel in any danger during this visit but in fact felt and saw

a strong sense of community."

Public health doctoral student Audrey Stevenson MS’90 MPH’04 comments: "We saw a variety of health conditions cases of drug-resistant tuberculosis, many patients with AIDS and multiple concomitant diseases, chest x-rays of a patient who had avian fl u, and many malaria patients. The country does a very good job in the diagnosis and management of malaria.

"We had the opportunity to learn the diagnosis and clinical manifestations

of leprosy," she continues. "In the U.S. we are beginning

to see cases of vector-borne illnesses [diseases spread by insects] that

were previously unheard of here. Take West Nile Virus, for example; prior

to 1999 we didn’t have human cases of this disease

[in the U.S.]. We are beginning to see a reemergence of some diseases

and importation of others. It was very educational to have the opportunity

of learning from experts in the identifi cation and management of many

diseases that we may begin to see here."

UPAP has been offering international programs for about 10 years, chiefl y in Papua New Guinea. When that arrangement expired, the program opted for Thailand, where UPAP faculty member Doug Barker lives and was able to develop an efficient program.

This was the first program in Thailand; a new crop of students will travel there again in January. Although UPAP alumni have started a fund, students bear all their own costs.

In some of the rural areas, students found that families of the patients provided much of the palliative care. In an AIDS hospice they visited, many of the daily activities were directed by other patients.

Stevenson observes: "Care is provided in a community environment where the patients form groups that look after one another," adding that many of the clinics train and employ members of the community, which forges a cultural link between them and the town.

Although the level of sophistication varied from one program to another, Stevenson was generally impressed by the cutting-edge research and approaches to vector-borne illnesses and chest diseases, learning of research that could be applied internationally. "In other areas, such as maternal and children’s health, the approach is more basic," she says. "[Thailand] has more health issues than resources. However, they do very well with those resources that they have."

Over the period of weeks he spent in Thailand, public health professor Han Kim MS’99 frequently observed a seamless integration between clinical medicine and public health. While touring the slums or the border areas where refugees interface with established populations, he says he found that "what the Thais have been able to do with limited resources is pretty admirable, specifi cally in the areas of HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis and malaria."

Lyle VanOrman, who is working on a master’s in public health, underwent acupuncture treatment from a retired Chinese doctor at the Thai Chinese Medical Cooperation Center. (VanOrman broke his back two years ago and receives electrical stimulation treatments for residual calf muscle paralysis.) "Eight needles were placed in my lower back, leg and foot," he explains. "When the last needle was inserted, I experienced the same type of shock sensation in my foot and ankle as I do when using the electrical stimulator. I’m a believer." The patients there told VanOrman that they had tried Western medicine with unsuccessful results but had experienced dramatic improvement since coming to the Chinese center. Adds VanOrman: "Normally a patient receives a series of 10 acupuncture treatments, and I would seek the next nine here if I could afford them. Unfortunately, few insurance companies recognize the effi cacy of Eastern medical practices." As a result of his experience, VanOrman is interested in pursuing a career in international health.

The UPAP students also observed acupressure, cupping and herbal steam treatments, and toured a pharmacy stocked with more than 600 natural remedies—nuts, seeds, leaves, and bark—used raw, soaked or roasted, altering their chemical properties, to treat illness. In fact, the Department for the Development of Traditional Thai Medicine offers a degree in natural medicine. "If the United States could get a better grasp on regulation of herbal medicine," VanOrman says, "we could experience the positive outcomes associated with natural approaches to medicine."

What do the Thai healthcare professionals get from this exchange? Since Thailand doesn’t recognize physician assistant certifi cation, the students were allowed to observe but not to treat patients. Instead, they brought their education and experience to the process. Pedersen explains that Thai physicians like to showcase their expertise to the students and appreciate having a partnership with an American university. Ultimately, he says, they would like to bring Thai healthcare professionals to the United States.

Crouse’s most interesting exchange took place in a Buddhist temple where a Dutch organization had opened an AIDS hospice. Until recently, it has been a place where people went to die. Now, thanks to anti-retroviral medications provided by the Dutch and the Buddhist monks’ fund-raising, the patients can survive. The attending Dutch physician showed Crouse a patient who was losing his vision and asked Crouse if he could see into the back of the eye (the retina) with an ophthalmoscope. The physician suspected a devastating condition, cytomegalovirus, and although he could recognize and describe the appearance of the virus, he had trouble identifying it in this patient. Crouse, for his part, had never seen cytomegalovirus firsthand but was adept at examining the retina. So he examined it and, based on the physician’s description, determined that the patient did not have the virus. Afterwards the physician took Crouse to another ward and together they examined a patient who, unfortunately, did.

Crouse comments: "In the countries we go to, they’re looking for something sustainable—something that will help for the next 30 years, rather than quick fixes. It’s fine to diagnose hypertension and give a patient three months’ worth of meds, but what does he do when those meds run out? An exchange of knowledge will go much farther."

When Crouse arrived home from Thailand with a low-grade fever, rash, fatigue and diarrhea, he knew that he had contracted typhoid, a disease still common in the developing world, where it affects about 12.5 million people each year. As a result, he will be an even better diagnostician for future patients, and will have more empathy for those he treats. Crouse’s illness was gone after 10 days on antibiotics, but the knowledge he gained in Thailand will stay with him much longer.

—Kim Hancey Duffy BS’84 BFA’99 is a freelance writer.

Her husband relates remarkable stories from his four trips to Vietnam

on healthcare projects; she plans to finagle a future invitation.

More of Dr. Kim’s photos are available at http://hankim.typepad.com.