| Vol.

13. No. 3 |

Winter

2003 |

by J.D. Davis

Though their mothers may be miles away, athletes at the University of Utah are constantly reminded, by a team of motherly influences, to get their chores done in the weight room, take care of their bodies, and eat right.

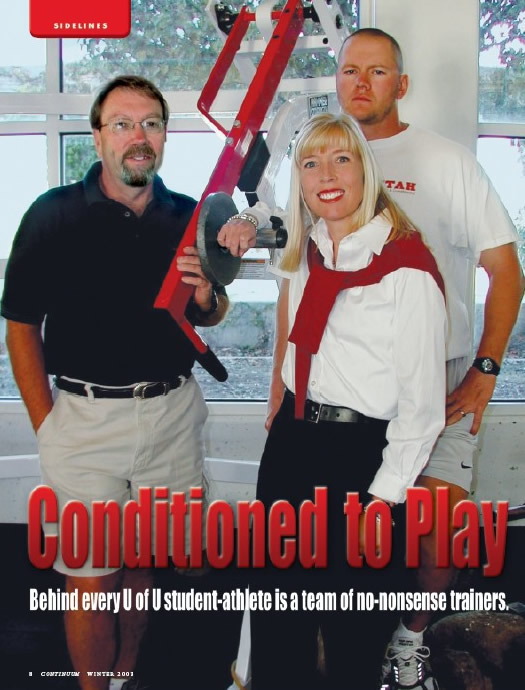

Meet Bill Bean MS’79 BS’86, director of sports medicine, Jason Veltkamp, head strength coach, and Claudia Wilson MS’97, sports nutritionist. The trio is the key to the U’s student-athletes’ getting stronger, staying healthy, and competing at their highest level.

When student-athletes sign a letter of intent to play at the University, much of their evaluation and fitness plan will be completed before they set foot on campus. High school injuries are noted and passed on to Bean; Veltkamp builds a program focusing on areas that need improved strength; and Wilson instructs athletes on the type and amount of food necessary for optimal growth and strength.

Coaches play a key role in this process. Not only do they evaluate recruits’ overall talent on the field, but they also assess players’ strengths and/or weaknesses in overall fitness and nutrition. With about 375 student-athletes to work with, coaches are in constant communication with trainers and medical staff. Having the strength facility and the medical treatment facility located in one place, the Dee Glen Smith Athletic Center, aids the collaborative effort on a specific athlete.

Before student-athletes can begin practice or workouts, they must complete a medical physical with a team doctor. Specialists are brought in to analyze previous or current injuries after an analysis is made by Bean. Nobody in the Ute athletic department has seen more athletes walk through the door than Bean. He has been the head trainer for more than 27 years and has seen amazing changes in medical diagnoses and treatment for athletes. When Bean started at the U, a new recruit may have arrived with a previously unknown condition. Now, an incoming student’s medical history beats him or her to campus. “Today we can get immediate information on injuries and get the student-athlete the best and quickest care,” says Bean.

The U athletic medical team must also comply with the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPPA). The new privacy rule prevents those who give medical treatment from releasing information on patients or their condition. “Players must sign a release form stating the U medical team and coaches can discuss injury information with the media,” notes Bean. How serious is the federal government about HIPPA? Fines for violations can run up to $250,000 with jail time.

After a student-athlete passes a physical exam and is cleared to work out, he or she is ready to hit the weights. Enter Veltkamp, whose demeanor lets you know he is dead serious about improving strength and speed. (If he were your mother, you would never, ever talk back.) First-year students learn quickly that when they step into the Smith facility, it’s time to get to work.

Each new student-athlete is assigned a program focusing on specific areas that need improvement, addressing issues such as body fat percentage, strength deficiencies, and injuries. “Our goal is not simply to make each person a better athlete; we also want a healthy athlete,” says Veltkamp.

|

No More Sedentary Employees… Faculty and staff at the U may not have the same conditioning needs as the student-athletes, but they can still take advantage of oncampus health resources: PEAK—The PEAK (Performance

Enhancement through Applied Knowledge) Academy offers a variety

of classes for full and part-time employees. The low-cost classes,

which include yoga, Pilates, cycling, and Nutrition Clinic—The College of Health’s Division of Foods and Nutrition operates a nutrition clinic, offering personal and corporate wellness programs, counseling, health screenings, and a monthly newsletter. Campus Recreation Services—“Campus Rec” operates the Field House, which has weights, handball/racquetball courts, a dance studio, tennis courts, and a jogging track; and the HPER (Health, Physical Education & Recreation) Complex, which houses basketball and volleyball gyms, weight rooms, racquetball courts, and the natatorium. Some fees and limited use times apply. Campus Rec’s Outdoor Recreation Program also provides rental equipment for backpacking, river running, canoeing, mountain biking, and skiing. |

In the beginning, Veltkamp’s staff works with each student- athlete individually to make sure that proper technique is used during workouts and that there is total focus on the job at hand. “Many of the injuries you see in a strength room are because there is a lapse in focus,” says Veltkamp.

Each sport has a unique weight-training program designed to build the strength and quickness necessary to compete in that particular activity at the highest level. New student-athletes are given separate workout programs before, during, and after the season.

Possibly the toughest job is that of nutritionist Claudia Wilson. If you thought it was hard getting your children to eat right, try working with 18-year-olds who are feeling overwhelmed by the new challenges that come with beginning college. Making nutritious meals must be programmed into the athlete’s daily routine. “Outside influences have a huge effect on nutrition for young people,” says Wilson. “If they are homesick, they probably are not eating right.”

Wilson’s approach is to build a relationship with each athlete so that she can discover issues that might affect proper nutrition. Wilson takes a motherly approach. Often, a stressful situation interferes in selecting nutritional foods. “Each athlete comes to college at a different maturity level. It’s important to build a level of trust so I am aware of outside influences affecting their overall health,” says Wilson.

Like the weight-training program, individual diets are created for each student-athlete. In addition, nutritional needs for male and female athletes are different. Women athletes at the U go through more nutritional screenings and are encouraged by Wilson to increase calcium—crucial to bone development— which has earned her the nickname, “The Calcium Queen.” A majority of the men focus on getting plenty of protein through diet and supplements.

Young athletes are bombarded with advertisements from companies promising increased strength, energy, and endurance through dietary supplements. Veltkamp and Wilson work in unison with each athlete to ensure they use supplements wisely. The NCAA has leveled the field for all colleges by creating rules that regulate additives, mostly focusing on the amount of protein they contain. Supplements can serve as a meal replacement because of the nutrients they contain and are a convenient way for busy student-athletes to get proper nutrition.

Most first-year athletes live in the Heritage Commons residential living complex. The variety of foods available there allows them to get the necessary nutrients. But it takes planning. For example, a new recruit in the men’s basketball program, enduring a Rick Majerus practice, can burn 5,000 to 6,000 calories a day. “If you haven’t eaten right that day or you skipped a meal, it will show in practice,” says Wilson. She adds that it’s normally after athletes’ first year that getting the proper nutrition becomes an issue, because they often move out of the dorms and into apartments, and must buy groceries. “I have to constantly stay on them because it’s easier for a 19-year-old to get fast food instead of going to the grocery store,” she notes.

In addition to proper training and nutrition, Bean and his staff constantly stress the importance of drinking water and hydrating the body. New student-athletes have probably never experienced the intensity of a typical practice for a Division I sport. Trainers have to remind beginning athletes to replace fluids before, during, and after workouts. During twice-a-day football practices in the heat of the summer, players must carry a water bottle to team meetings. On the hottest days, the football team will consume 100 gallons of water, 100 gallons of Poweraid, and use 100 gallons of ice, placed in tubs to provide a quick cooldown.

How important is it to follow through on instruction from these behind-the-scenes individuals? If students miss a workout, rehabilitation, or training session, their head coach will be notified—resulting in extra laps or sets of stairs. After a few “suicide sprints,” most student-athletes wish for the good old days, when a misstep merely meant being grounded.

—J.D. Davis BS’86 is a frequent contributor to Continuum.

Going

the Distance: One Runner's Story

Going

the Distance: One Runner's Story

When coaches speak of the need for an incoming recruit to gain strength and conditioning, we often imagine an 18-year-old offensive lineman power lifting and consuming large quantities of food to achieve the necessary bulk for his position.

But all student-athletes need to increase strength and power. While some need bulk, many others focus their training on speed and fitness.

Take U of U track athlete Nellie Hammons, who competes in the 400 and 800 meters. As a redshirt freshman, Hammons placed a respectable eighth in the Mountain West Conference championships in the 800 meters with a time of 2:17. Now, as a sophomore, she is regularly running times of 2:06. She broke the school record four times last year and was the lone Ute qualifier for the NCAA Championships. So…how did she do it?

Hammons came to the U with a typical runner’s build. “I looked like a runner and had trained lots, but I didn’t know how to get to the next level of fitness,” she says. Enter Brian Appell, head cross-country coach, who brought a structured strength and conditioning plan to the U’s track team.

Hammons’ strength training focuses on the “core” body—the large muscle groups in the abdomen and back. Creating a strong core enables the athlete to then work on specialty exercises that concentrate on the smaller muscles critical to individual success. “I am focusing on being a more efficient runner by strengthening my hip flexors, which keeps my knees and in the proper position,” says Hammons.

She has also dramatically changed eating habits from a “whatever-and-whenever” diet to a regimented protein-based diet. “I try to eat meat once a week and on soy-based products for as much protein as possible,” Hammons says. She is also taking a daily multivitamin and a calcium supplement to help her maintain bone growth and strength.

Hammons might not look much different than when she first stepped on campus, but her new diet and workout have had several key benefits. Most obvious is her performance on the track—the clock doesn’t lie. Her confidence has increased, as well. “With each new improvement in my fitness, my confidence grows, which makes me want to work even harder,” she says. And an unexpected side effect has been increased energy the English major has her studies. “When I’m eating well, my head is always clear, even when my body may be tired,” she adds.

Indeed, Hammons’ recent naming the NCAA all-academic track team is proof that her workout and eating program has her on the right track.