Vol. 15 No. 1 |

Summer 2005 |

Jaymes Myers knew that his announcement wasn’t going to go over well. After all, as a freshman chemistry major at the University of Utah, Myers had been groomed for most of his life to be right where he was. He was the first person in his family to attend college, studying in a field his parents felt would lead directly into a lucrative career—a career they hoped would elevate him beyond their own financial station.

Those hopes dimmed, however, when Myers sat his parents down and announced a switch: Goodbye chemistry, hello speech communication.

“Well,” said his mother, echoing a common perception of the humanities, “there’s no money in that.”

Maybe it happened during the tech boom of the late ’90s, when ethics were sometimes sidelined in pursuit of the next great gadget and another uptick on the NASDAQ. Or maybe it was much earlier, when Grog skipped his clan’s woolly mammoth feast to play with the new wheel he’d carved out of a rock. Somewhere along the line, we put a little more value on technology, and a little less on humanity.

In many ways, higher education has followed suit, becoming less about germinating well-rounded, thoughtful citizens and more about cranking out employees. Eschewing the liberal arts core on which they were founded, many universities promote more “glamorous” (read: revenue-generating) fields like the applied sciences, engineering, technology, and business. The result on campuses nationwide is humanities colleges that are largely marginalized, both in terms of funding and scholarly prestige.

Not so at the U, where a concerted effort in recent years has put a new face on the College of Humanities. Under the direction of an impassioned dean, the college has—in just three years—increased funding by more than 450 percent, launched cutting-edge programs that are the first of their kind in the country, sponsored groundbreaking community initiatives, and generally raised the profile and morale of the college.

On one level, the devalued status of the humanities—which at the U include the departments of Communication, English, History, Languages & Literature, Linguistics, and Philosophy—may simply be a sign of the times. In 1870, just 52,000 students were enrolled in colleges in the United States—a mere .14 percent of the total population. Today, that number is around 16 million, with a quarter of all U.S. citizens age 25 and older holding undergraduate degrees. Higher education, once a privilege of the well-heeled and well-bred, is now a commodity for the masses. And while the wealthy could afford to indulge in the high-minded pursuits of philosophy and literature, the masses needed jobs. Consequently, universities gradually drifted from a broad-based liberal arts model to a more narrowly focused vocational one.

Funding, too, shifted away from the humanities. Appropriations for the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH), the primary federal source for humanities funding, peaked at $354.3 million in 1979. In 2004, the NEH budget was $135.3 million, $219 million less than a quarter-century ago.

|

U

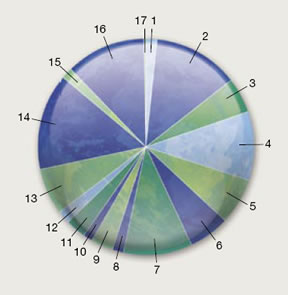

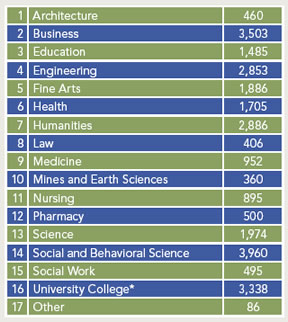

OF U FALL 2004

* Newly admitted students are automatically enrolled in University College until they are admitted to the department or college of their chosen major. |

Despite these decreases in both funding and prestige, enrollment in the humanities has remained relatively stable. As U of U linguistics professor Lyle Campbell points out, humanities colleges across the country often have the largest proportion of students taking the largest proportion of classes.

“If you’re simply looking at student demand,” says Campbell, “then the humanities are in great shape. If you’re looking at who’s bringing in the money, then humanities have always had kind of a liability, because in the humanities we just don’t have access to those consultancies and private accounts that you do in law, engineering, medicine, et cetera.”

This was exactly the predicament Robert Newman found upon taking over as the humanities dean in 2001. At the time, the college received just one tenth of one percent of the University’s total grant monies, even while it conferred 20 percent of the University’s diplomas. Since Humanities is the third-largest college on campus, this exposed a huge disconnect between funding and student demand, further highlighted by the fact that every undergraduate who enters the University enrolls in humanities classes at some time during the course of his or her studies.

Newman immediately initiated a reformation, starting from the ground up. “We needed a cultural change in the college,” he says. “There was the sense that in the humanities, you kind of waited at the back of the line for things to happen. I think people needed to learn to believe in themselves and the significance of what they were doing.”

And what they were doing, in Newman’s view, was nothing less than providing the principled foundation for the University and society as a whole. At its core, the humanities attempt to decipher and describe what it means to be human. In that sense, they have a distinct advantage over disciplines bound by scientific rules and mathematical formulas. The skills learned in humanities can be applied to virtually any vocation.

“I think any good scientist, any good engineer, any successful corporate executive or attorney,” says Newman, “will tell you that their experience and their learning in their basic liberal arts core has been fundamental to their success. Because what we do, what we teach, what we study is how to think creatively, comparatively, and systematically. We also teach how to communicate effectively and how to process life experience in ways that are fulfilling and ethical. And therefore, there’s no question in my mind that the humanities are fundamental for success in a democratic society.”

To get this message out, the college launched a number of highly successful community-based initiatives designed to reconnect the humanities with the community at large. The college sponsored an 80-team Latino youth soccer league in Salt Lake City. It launched the Humanities Happy Hour, a casual, lively monthly lecture series held at Squatters Pub. It formed The Renaissance Guild, an intellectual forum in which citizens discuss literary works. And it created Community Scholarships for Diversity, aimed at providing funds to first-generation college students.

|

Do you agree that the humanities have been marginalized, both on a national level and at the U of U? On a national scale, yes. My experience here, under both the Machen and the Young administrations, and working very closely with [Senior Vice President of Academic Affairs] Dave Pershing, has been a very positive one. I think a lot of the reason that I came here, and was brought here, was because of their desire to elevate the humanities. What do you love most about your job? I see my job as very, very challenging in all the right ways. If you want to put it in crude business terms, I have the leadership role for selling a product in which I passionately believe. And that’s great. Also, I work with really concerned, energetic, thoughtful, smart people who have excellent values. What is the least enjoyable part? I guess I would say sometimes battling narrow-minded perspectives and perceptions of what a university is about, and what the humanities do. So, flippant remarks like, ‘All humanities majors are going to be flipping burgers at McDonald’s’ I think are ill-informed. And that’s frustrating. Can society at large ever be convinced that the humanities are equally important to society as technology? I don’t know about the outcome, but I certainly think it’s a noble endeavor. Where do they work? College of Humanities graduates routinely enter the following fields:

|

“We’re reaching out to the community like this school has never seen before,” says Tim McInnis, hired in 2002 as assistant dean in charge of external and alumni relations. “We probably sponsor—by ‘we’ I mean all of the college departments and the dean’s office—more public lecture series than any other college on campus, by far. We really do feel that we need to be out in the community, sharing ideas.”

On top of this wave of community outreach, the College of Humanities has introduced a series of groundbreaking scholarly programs, with an emphasis on international and interdisciplinary studies. Under the traditional model of higher education, there are distinct boundaries between disciplines— chemistry and history, for example, would never intermingle. Under an interdisciplinary approach, the humanities have the opportunity to inform debates that might have previously been the exclusive domain of science, economics, or ecology.

The importance of this type of approach is lucidly illustrated by McInnis.

“Wouldn’t it have been nice if there had been an ethicist

at Los Alamos?” he asks, referring to the nuclear testing facility

that developed the atomic bombs dropped on Japan in World War II.

Among the College of Humanities’ new programs aimed at bridging

the gap between disciplines is a new master’s degree in Environmental

Humanities, the first of its kind in the country. The

inaugural class of graduate students will enter the program this fall.

This unique, interdisciplinary approach will look at environmental issues

through an “ethical, historical, and cultural” lens.

University President Michael Young, in a new promotional video for the College of Humanities, sums up the need to bring a human voice to environmental debates. “If you think of the environment—an area in which we have wonderful programs here at the University of Utah—we can create extraordinary environments or we can destroy environments, but the science doesn’t tell us which to do. The humanities tell us how to think about and relate to that environment.”

All of these ambitious scholarly and community initiatives have translated into something that is not always associated with the humanities: money.

In 2002, grants and donations to the College of Humanities totaled just $477,612. By 2004 that figure was nearly $2 million. As of mid-2005, the college had taken in $2,675,775, a 460 percent increase over 2002. The number of new donors that the college attracted jumped from 281 in 2002 to 483 in 2004, a 72 percent increase.

Grant funding within the college has been particularly impressive, as faculty members have increased the number and dollar amounts of their grant requests.

Lyle Campbell attributes much of this increase directly to Dean Newman. “I think he’s gotten the idea of the need out to faculty members in our college,” says Campbell. “And more people are applying. But he’s also very good at providing the information and mentoring so that people who in the past might not have actually asked for research money, or even attempted research projects, now are doing it.”

The numbers certainly support that claim. The college submitted just 10 grant proposals in 1999. That number jumped to 65 in 2004. Funds awarded went from $45,493 in 2001 to $1,202,053 in 2004.

Numbers like these go a long way toward reversing an ingrained perception that the humanities are—as Robert Newman puts it—“the welfare state” of the university. The influx of hard cash serves notice that the humanities, in addition to being the scholarly core of a university, can also be a vital cog in its economic engine.

“What this dean and his leadership team of chairs and directors have been able to do,” says McInnis, summing up the unprecedented revitalization effort over the last three years, “is basically reclaim the place of the humanities as the centerpiece of this university.”

That’s good news for students like Myers, who is now a junior and on track to graduate next year with his degree in speech communication and a minor in ethnic studies. In three years he has seen both tangible and intangible benefits from the humanities’ resurgence, including an energized faculty that is actively seeking to connect with students.

Most of all, though, he is comfortable knowing that he has found his home in the humanities—that what he is doing has purpose.

“I think what I’m learning, and what the humanities have made me passionate about,” says Myers, “is understanding people’s experiences. And how that translates into my own goal is really becoming a global citizen, becoming someone who can affect and change society for the better.”

Somehow, there’s got to be a future in that.

—Brett Hullinger is a freelance writer living in Salt Lake City.

Q&A:

Dean Newman

Q&A:

Dean Newman