| Vol. 14 No. 1 | Summer 2004 |

Ever seen a cat stuck in a room with a couple of kids? The cat’s on guard, uncomfortable, leery of the kids’ intentions. At the first sign of an open door, the cat’s outta there.

My first experience with Urban Meyer was like that. And, no, I wasn’t the cat.

It was May 2003, and the new coach of Utah football was cornered in a studio, shooting his part in the soon-to-air television commercials I had written. After we shot a scene of an overwhelmed defensive back coping with four receivers flooding his zone, the idea was to cut back to Urban, who would offer the rhetorical question, “Who you gonna cover?”

The first takes were flat. So I said, “Maybe you could say the line as if it’s a loaded question—as if you know you have the guy beaten. Maybe with a kind of smirk on your face.”

“I don’t smirk.”

Okaaaaay…moving right along.

At

the end of the spot, Urban was to describe the offense as a “fast

break on turf.” We cut to a beautiful shot of a wide receiver dunking

over the goalpost after scoring a touchdown. Then we wanted to cut back

to Urban saying, offhandedly, “Well, without the dunking.”

I asked Urban to deliver the line as if he were laughing to himself.

At

the end of the spot, Urban was to describe the offense as a “fast

break on turf.” We cut to a beautiful shot of a wide receiver dunking

over the goalpost after scoring a touchdown. Then we wanted to cut back

to Urban saying, offhandedly, “Well, without the dunking.”

I asked Urban to deliver the line as if he were laughing to himself.

“I don’t really laugh to myself.”

As the takes mounted and the session crept into its fifth hour, I became the aforementioned kid and Urban was the tormented cat, looking for a way out of the room. Was this silliness of a TV commercial ever going to end?

It was then I knew that the future of Utah football was in good hands. There would be no more missed assignments. No more clock mismanagement. No more losses due to lapses in concentration.

This guy meant business.

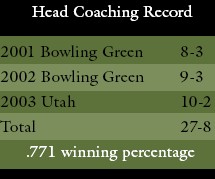

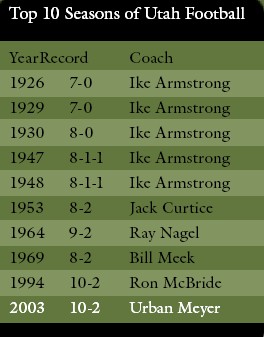

That businesslike attention to detail showed itself throughout the Utes’ amazing 10-2 season. Of those 10 wins, six were decided on the last play. Of those six, only Texas A&M was a loss.

Sitting in his office nine months after our studio session, Urban says he is still irritated by that A&M loss, noting that he hadn’t prepared the team for every scenario. “I guarantee that will never happen again,” he says quietly.

This is a good time of year for Urban Meyer. Since the blur of summer two-a-day practices, the season and bowl game, and the circus of recruiting, he has barely had a moment to take a breath. Now it’s time to evaluate the season, the staff, the players, even the plays. He has a coach from the Minnesota Vikings coming to town to look over the offense and offer suggestions. And on the home front, he can reenter family life, attending 13-year-old Nicki’s club volleyball games and 10-year-old Gigi’s basketball games (she’s the MVP of her team, a boys’ basketball team), and hanging out with five-year-old Nate.

“I really like this time of year,” he says.

So

does his wife, Shelley. They met toward the end of her freshman year at

a Sigma Chi Derby Social at the University of Cincinnati. He was a football

player from Ashtabula, a small town on Lake Erie. She was from Chillicothe,

a small farming town east of Cincinnati. She “sort of” had

an old high school boyfriend back home. Not for long. Urban and Shelley

have been a team ever since.

So

does his wife, Shelley. They met toward the end of her freshman year at

a Sigma Chi Derby Social at the University of Cincinnati. He was a football

player from Ashtabula, a small town on Lake Erie. She was from Chillicothe,

a small farming town east of Cincinnati. She “sort of” had

an old high school boyfriend back home. Not for long. Urban and Shelley

have been a team ever since.

This is the time of year Shelley and the kids get the coach back from his other family. “He is gone so much during the season,” she explains. “Sometimes he’ll leave at 6 a.m. and won’t get home until 10:30 at night. By the end of recruiting, we are really ready to get away.”

But not just yet. First comes spring practice, followed by a series of high school coaching clinics. But then comes July and the annual family vacation. Where? “Sand, palm trees, and umbrella drinks,” Shelley laughs. “We have no interest in doing an Alaskan cruise.” Hawaii is usually the spot. They did try Europe one time, but the response was lukewarm, literally. “There’s no beach and no ice for your drinks,” she says.

|

“I love the

clean environment, the culture, the dry heat.” |

All Ute fans who think this could be the beginning of Camelot for Utah

football probably have Shelley to thank for that.

“I’d been putting pressure on Urban for seven years [five at Notre Dame, two at Bowling Green] to get us back out west or down south,” she says proudly. “When I was in Fort Collins [where Urban was an assistant coach with Colorado State], I absolutely loved it. Growing up in the Midwest, once you come out here, you don’t want to go back there.”

Go west, young man, she said. Then came the Bowling Green offer, a chance to be head coach. While Shelley could appreciate the opportunity, she wasn’t fond of the due-east compass direction from South Bend to Bowling Green. But they went, almost instantly turning a failing program into a conquering David.

Shelley’s focus never turned from the West, though. So when Utah called, she told Urban, “You’ve got to go look at that one.” As she remembers, “It was hard to think about leaving [Bowling Green] after only two years, but all I could think about was getting back to the mountains, back to the sun, back to activity in the winter instead of just hibernating. It’s so gorgeous here.”

Urban agrees. “I love the clean environment, the culture, the dry heat. My rule is that if you’re going to leave a good place, you have to go to a better one. We did that here.”

Thirteen-year-old

Nicki wasn’t as thrilled. “She immediately screamed and cried,”

says Shelley. “She knew exactly how long we’d been in Bowling

Green, a year and four months. It was the end of the world.” One

of Gigi’s friends even called her a traitor. Having moved only twice

since having children—unusual for an up-and-coming coach—this

was the first time Urban had seen the negative side of it, and he considered

turning the offer down.

Thirteen-year-old

Nicki wasn’t as thrilled. “She immediately screamed and cried,”

says Shelley. “She knew exactly how long we’d been in Bowling

Green, a year and four months. It was the end of the world.” One

of Gigi’s friends even called her a traitor. Having moved only twice

since having children—unusual for an up-and-coming coach—this

was the first time Urban had seen the negative side of it, and he considered

turning the offer down.

Shelley saved the day, at least for Ute fans. She told Urban the kids “would be fine in a day.” And after an initial trip in December that included a Runnin’ Utes basketball game (complete with Meyer family introductions at halftime) and tours of ski areas, the sadness turned to excitement.

Now the two girls are budding snowboarding pros and Nate has taken his first ski lessons. For those who fret that Urban will leave for greener pastures, there is hope. The one day he joked about moving, it didn’t go over well with the smaller set. “They would be done with us if we ever even talked about moving,” Shelley explains. “They love it. They’ve just jumped right in.”

Although Urban and Shelley knew something about Utah, having traveled and recruited here while at Colorado State, their friends had some reservations. “There are so many misperceptions back in the Midwest about living in Utah because it’s predominantly LDS,” Shelley says. “All I heard was, ‘They won’t include you in anything.’ But then you come out here and people are just great. Of course, 10-2 will make everybody happy.”

Still,

friends gave Urban his share of standard Utah jokes once he accepted the

offer—things like, “So, how many wives do you get in your

contract?” Shelley’s take on that? “He couldn’t

handle any more wives. No way.”

Still,

friends gave Urban his share of standard Utah jokes once he accepted the

offer—things like, “So, how many wives do you get in your

contract?” Shelley’s take on that? “He couldn’t

handle any more wives. No way.”

Urban’s well-known intensity is matched by Shelley’s own high energy level. Running the household during the long hours of Division I football coaching is only the start. With a bachelor’s degree in nursing from Cincinnati, Shelley returned to school during the Colorado tenure to get a master’s in psychiatric nursing from the University of Colorado. She has been a psychiatric advanced practice nurse since 1994 and currently works part-time in that capacity at the U’s Neuropsychiatric Institute. She is also a clinical instructor for the College of Nursing. If that weren’t enough, she teaches aerobics and indoor cycling classes at local gyms. And you thought two-a-days were tough.

When it comes to the kids, you’d figure that Mr. Discipline on the football field would play that same role at home. Urban says he does “have high expectations and expects high achievement, just like I coach.” But he readily admits his nickname in these matters is “Sugar.” “Whatever the kids want, I’ll give it to them,” he says. “All they have to do is call me. There’s no doubt who’s the boss.”

Although both Shelley and Urban were raised in strict households, Urban reserves his discipline for his other team. Not so with Shelley. “When Nicki comes home and says, ‘You are the only mom in class who won’t let me see that movie,’ I want to high-five somebody,” she says. “I tell her I take that as a compliment.”

Both

are ultra-competitive. Shelley gleefully recounts the story of a Memorial

Day race they both ran in Colorado, called the “Bolder Boulder.”

Having run it before, she wanted to take the 10K race at a fun pace. Urban,

on the other hand, wanted to race her. When he started off at a fast pace,

she cautioned, “You can’t run this fast. We’ll never

make it.” His comeback: “Oh come on, you whiny butt.”

Wrong comeback. Shelley let him run ahead, and then ran her own pace.

After a couple of miles, she was closing on him. Then she worked her way

around him, hiding in the mass of people. He never knew she had passed

him—until he crossed the finish line and saw her waiting for him.

Both

are ultra-competitive. Shelley gleefully recounts the story of a Memorial

Day race they both ran in Colorado, called the “Bolder Boulder.”

Having run it before, she wanted to take the 10K race at a fun pace. Urban,

on the other hand, wanted to race her. When he started off at a fast pace,

she cautioned, “You can’t run this fast. We’ll never

make it.” His comeback: “Oh come on, you whiny butt.”

Wrong comeback. Shelley let him run ahead, and then ran her own pace.

After a couple of miles, she was closing on him. Then she worked her way

around him, hiding in the mass of people. He never knew she had passed

him—until he crossed the finish line and saw her waiting for him.

“His mouth just dropped,” she laughs, “and he started yelling NOOOOOO! We just had the best laugh. It was the greatest victory of all time for women, I’m tellin’ you.”

But it’s not all laughs when it comes to the business of winning on the football field. During the week of a big game, Urban can’t sleep, can’t eat, and feels nauseous. “Here I am a psych nurse,” says Shelley. “You’d think I’d be able to help him more than I do.”

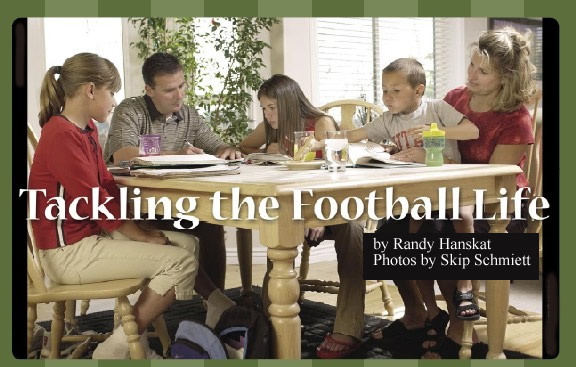

Thursday

night is the one night of release. Urban views the team as family. So

on Thursdays, they go out as one really big family. Players, coaches,

wives, even kids all have dinner together. “I think we care more

about our players than any other coaching staff,” Urban says proudly.

Thursday

night is the one night of release. Urban views the team as family. So

on Thursdays, they go out as one really big family. Players, coaches,

wives, even kids all have dinner together. “I think we care more

about our players than any other coaching staff,” Urban says proudly.

Friday dawns and the pressure returns, building until kickoff. But all is well when a victory is notched. Shelley explains, “It’s like a big weight is lifted. It feels like all the work paid off. When you lose, it doesn’t feel like the work paid off, even if you just lost to No. 1. I can’t even explain the feeling of winning the game to people who have no interest in athletics.”

Post-win, the Meyer house then becomes an open house. People bring food;

it’s one big party. “And you can watch other games, knowing

that they have to worry about winning and you already won yours,”

Shelley says.

Occasionally, there’s the other side, the loss. “I just can’t

function after a loss,” Urban says. “I can’t do anything.

I take the losses too hard.” Neither he nor Shelley can sleep.

It’s not life and death, but it’s close, says Shelley. “Any lay person would say, ‘It’s just a football game.’ A football game is entertainment for him. For us, it is business. It is [Urban’s] job. If he loses too many, he gets fired. People forget that. We’re paid to win football games.”

Last fall was virtually all open houses and happy Sunday mornings. For Urban, the high point of the season was when the student body came out in force. “That was when I knew we owned the place, because the students motivated the team,” he says. “The players didn’t want to let them down. Whenever there was an honor or award, the first thing they’d do was take it over to the student section [formally known as The MUSS].”

Students are Urban’s focus. He has dozens of great ideas on how to further engage the student body of this so-called commuter campus. Next season, a student—known as the “Utah Man”—will even be added to the kickoff team, a la Texas A&M’s 12th Man.

Now if he could only avoid having to do those silly TV spots again.

—Randy Hanksat is a writer in University Marketing & Communications.