Powell and Stegner: Challenging Western Myths

“Water is the true wealth in a dry land; without it, land is

worthless or nearly so.” —Wallace Stegner

Ponder

this: Utah is in its fourth consecutive year of drought and there is talk

of water rationing this summer. And even if the drought is broken the

threat of its return is ever present in the arid West. With an annual

average rainfall of 13 inches, Utah is the second driest state in the

nation (next to Nevada). Nevertheless, Utahns are notorious water consumers,

slurping up 262 gallons of water a day, which amounts to the second highest

per capita water use in the country.

Ponder

this: Utah is in its fourth consecutive year of drought and there is talk

of water rationing this summer. And even if the drought is broken the

threat of its return is ever present in the arid West. With an annual

average rainfall of 13 inches, Utah is the second driest state in the

nation (next to Nevada). Nevertheless, Utahns are notorious water consumers,

slurping up 262 gallons of water a day, which amounts to the second highest

per capita water use in the country.

With the steady increase in the state’s population, Utahns are becoming

ever more dependent on the damming up and storing of water. Now, with

the forecast that the state will add a million more people in just 20

years, an obvious question arises: how can such a massive population increase

be accommodated?

In attempt to answer this question, the University undertook various initiatives

this past year covering a wide range of water-related issues. One of these

was the Seventh Annual Symposium of the Stegner Center for Land, Resources

and the Environment at the S. J. Quinney College of Law, “Powell

& Stegner: Fifty Years after The Hundredth Meridian.”

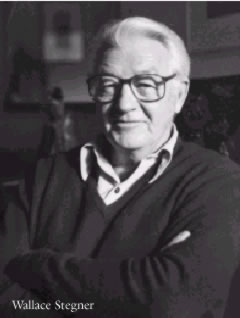

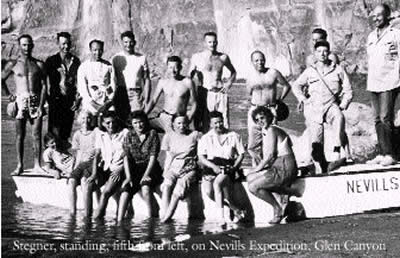

The focus of the symposium was Pulitzer Prize-winning author Wallace Stegner

BA’30 (see Continuum, Winter 1995-96) and his internationally

acclaimed book, Beyond the Hundredth Meridian: John Wesley Powell and

the Second Opening of the West. The symposium marked the 100th anniversary

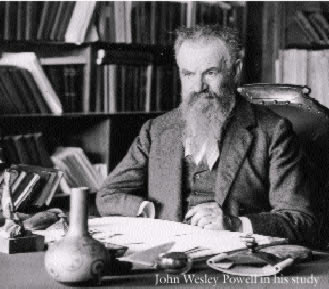

of the death of Powell—explorer, scientist, and adventurer—who

left an indelible mark on the history of the United States, particularly

on the course of events in the West.

The story of water in the West can be traced back to the summer of 1869,

when Major Powell, a one-armed Civil War veteran, led a small group of

amateur scientists and mountain men on an exploration of the Green and

Colorado river regions, an area little known by non-Indians. The only

feasible way to gain access through the Grand Canyon of the Colorado—279

miles of roiling rapids and unknown, uncharted territory—was by boat,

which no European American had ever attempted.

It seemed

unlikely that Powell and his team of tenderfoots would emerge with anything

more useful than the saving of their skins. Ultimately, however, Powell

did reappear, after a harrowing journey and the loss of a few good men.

The information he had gathered would have major implications for the

future development of the western United States.

It seemed

unlikely that Powell and his team of tenderfoots would emerge with anything

more useful than the saving of their skins. Ultimately, however, Powell

did reappear, after a harrowing journey and the loss of a few good men.

The information he had gathered would have major implications for the

future development of the western United States.

Seven years and another trip down the Colorado later, Powell submitted

his findings to the federal government in A Report on the Lands of

the Arid Region of the United States, with a More Detailed Account of

the Lands of Utah. The 200-page report outlined his recommendations

for the development of the region. At the same time, it challenged the

prevailing views of the West, chipping away at mountain-man myths and

romantic fantasies given currency by railroad entrepreneurs, land speculators,

developers, and politicians of all stripes.

The report was widely disputed by self-styled Western “experts”

who saw the region as a land of infinite open space and untapped natural

resources ripe for development. The West’s destiny, they claimed

in chorus, was manifest.

Leading the choir was the territorial governor of Colorado, William Gilpin,

whose voice resonated all the way to Washington. Stegner describes Gilpin

as “[a man who] saw the West through a blaze of mystical fervor,

as part of a grand geopolitical design, the overture to global harmony;

and his conception of its resources and its future for a home of millions

was as grandiose as his rhetoric, as unlimited as his faith, as splendid

as his capacity for inaccuracy.” The clash between opposing views—Powell

vs. Gilpin, the practical realists vs. the fabulists—continues to

resound to this day.

It is this

state of affairs that Stegner examines in Hundredth Meridian (the

invisible boundary running through Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma that

separates the eastern part of the United States, where annual rainfall

is over 20 inches, and the western part, where it is less.) Published

almost 50 years ago, the book has served as a landmark in American literature

ever since. It has drawn attention to misconceptions about the West and

the fragility of its resources, spurring a fledgling environmental movement

that has gathered force to become an authoritative, if often contested,

voice in the contemporary West.

It is this

state of affairs that Stegner examines in Hundredth Meridian (the

invisible boundary running through Nebraska, Kansas, and Oklahoma that

separates the eastern part of the United States, where annual rainfall

is over 20 inches, and the western part, where it is less.) Published

almost 50 years ago, the book has served as a landmark in American literature

ever since. It has drawn attention to misconceptions about the West and

the fragility of its resources, spurring a fledgling environmental movement

that has gathered force to become an authoritative, if often contested,

voice in the contemporary West.

The interplay between Powell and Stegner was the focal point of the Stegner

Center symposium. Comments Keith Bartholomew, the center’s associate

director and organizer of the event, “Both Powell and Stegner, in

their own ways and own times, had a profound impact on the way the West

is viewed, both inside and outside of Utah. Powell was an explorer of

geography, Stegner an explorer of literature; together they defined the

modern image of the American West.”

Keynote speaker Charles Wilkinson, Distinguished University Professor

and Moses Lasky Professor of Law at the University of Colorado, observes,

“Powell was perhaps the greatest Western thinker of the 19th century

and Stegner was probably the greatest of the 20th. Stegner explained the

real history of the West—the shortsightedness and the treachery,

but also the civility and cooperation that were the truest and best Western

traditions.”

Powell essentially created a “blueprint for a dryland democracy,”

writes Stegner. He examined the area west of the 100th meridian—a

region of disputes, feuds, and misconceptions, where the “only unity

was the unity of little rain”—and proposed a program for development

that would take into consideration its topography and unique characteristics,

in particular its limited water resources.

By so doing, Powell challenged the popularly held belief that “rain

follows the plow”—that is, that tilling the soil actually increases

the annual rainfall, or that as the population grows, the moisture intensifies.

Fuzzy forecasting aside, this belief was inculcated by those, such as

Gilpin, who wished the myth into the popular imagination.

Growth and development were concepts that spurred the unprecedented westward

expansion of the 19th century, as embodied by Mormon pioneers who arrived

in the Great Salt Lake Valley in 1847. What they saw upon arrival was

a vast, desolate-looking land. Ever enterprising, the pioneers set up

a system of irrigation that would eventually “make the desert bloom,”

thereby establishing a pattern for other Western states to follow.

A century later, the population of Utah has blossomed to over two million

inhabitants and continues to grow exponentially. While this seems a drop

in the bucket compared to more densely populated regions of the world,

the fact is the shortage of water that already exists will obviously become

more severe as the population increases.

Water, water, everywhere…

“The subject of water in the West is a huge topic,” says Peter

H. DeLafosse, who, as chair of the 2002 Keepsake Committee of the Friends

of Marriott Library, is well versed on Stegner and Powell and their concern

over water issues. “You can’t talk about the West without considering

water.”

Indeed, the topic of water was widely dealt with at the U this past year.

The American West Center, under the direction of Daniel McCool, professor

of political science, has initiated a study of federal water policy, specifically

examining how national water objectives have changed from a policy focused

on structural solutions—such as dams, diversions, levees, and channelization—to

a policy emphasizing river restoration and ecosystem preservation, including,

in some cases, the removal of dams. While tearing down dams may seem to

fly in the face of water conservation, the opposite is true. Explains

McCool, “The idea is to move from water development, or structural

solutions, to water management—that is, using water more wisely.

For a century, political incentives were biased toward development regardless

of whether it made economic or ecological sense. This has resulted in

massive waste of water and money, and enormous damage to the environment.

As a result,” says McCool, “most of the West’s water resources

today are allocated to uses that are illogical and economically nonviable”—to

hay, for example, the West’s principle crop, which is a low-value

but high water-consuming crop. “In many cases,” he says, “the

water that is used to flood hay fields is worth more than the hay. And

if we didn’t heavily subsidize these uses, they would not occur.

Wise water management would price water at its market value, and public

waters would be used for public purposes such as recreation, parks, and

habitat preservation. This would be good for the economy, the taxpayers,

and the environment.”

University alumni and staff are involved in “Moving Waters: The Colorado

River and the West,” a project sponsored by the humanities councils

of the seven Western states that share the waters of the Colorado. The

project includes a traveling exhibit, a six-part radio series, a lecture,

and a reading and discussion program in each location, and explores crucial

issues regarding the human encounter with and use of the Colorado River

and its tributaries. Philip F. Notarianni BS’70 MA’72 PhD’80,

adjunct professor of ethnic studies, is the director for the Salt Lake

City programs, and Roy Webb BA’84 MS’91, multimedia archivist

at the Marriott Library, is a discussion leader on the University of Utah

Press publication, A Colorado River Reader, edited by Richard F.

Fleck. The public programs in Utah are being conducted in Salt Lake City,

Moab, and Vernal between April 2002 and September 2002. For more information,

check the project’s Web site at: www.movingwaters.org.

The Marriott Library is contributing to the study of water by proposing

to establish the Western Waters Digital Library (WWDL). According to Kenning

Arlitsch, head of Digital Technologies at the library, “The simple

vision for the WWDL is to create a digital library of water resources

that would act as a central repository for scholars, lawyers, corporations,

government organizations, and lay people.” The brainchild of Marriott

Library director Sarah Michalak and assistant director Greg Thompson,

the collection would house information in formats ranging from photographs,

text, maps, and manuscripts to audio and video holdings, and would cover

a complete range of informational areas, from geography, economics, and

environment to recreation, policy and planning.

The first installment of the WWDL is the diary and photographs from the

Galloway-Stone Expedition of 1909, considered by Colorado River historians

to be the first such river trip undertaken purely for pleasure. Nathaniel

Galloway’s diary, as well as photographs taken from the expedition,

can be viewed online at www.lib.utah.edu/digital/galloway.

Other online contributions by the library include more than 1,000 photographs

of Glen Canyon, which can be viewed on the Photograph Archives Web site

at www.lib.utah.edu/spc/photo,

keyword “Glen.”

WWDL is a cooperative effort by 28 major institutions west of the Mississippi, organized as the Greater Western Library Alliance (GWLA). The success of the proposal will be determined by September 2002.

Associate Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering Rand Decker BS’78 was recently named a co-recipient of the Bennion Center’s 2002 Public Service Professorship for his work on a broad initiative known as the Headwater Center, in collaboration with faculty at the University of Nevada at Las Vegas. The focus of the project is water resource management in the Colorado River Basin. “The center,” explains Decker, “will serve as an allocation resource. It is designed to be an objective, stand-apart arena in which the varied demands on water use can be assessed.”

An expert on snow hydrology (“85 percent of the Colorado River originates

from snow”), Decker says that one of the most compelling ideas associated

with the project, recently proposed by UNLV professor Greg Leavitt, is

to set up a K-12 school curriculum in natural resources with the idea

of teaching “personal allocation consumption,” where individuals

would learn early on that they need to be “self-policing” regarding

water usage.

Concludes Decker, “The Colorado River, already utilized at 100-plus

percent, will have more demands put on it as the Southwest continues to

grow. The need for a well thought out, overarching policy, including instructional

and technical considerations, will also grow. Utah is, literally, right

in the middle of this.”

Finally, the use (and misuse) of water was the focus of a three-part series,

“Soaking the Desert: The Story of Water in Utah,” broadcast

by KUER radio last winter. The program was reported, written, and produced

by Jenny Brundin and Vince Pearson and edited by Kat Snow, KUER news director.

The entire script is available online at www.kuer.org/water/readlisten/index.html.

“The story of water in Utah,” said Snow, narrating the program,

“is the story of a water system bloated with inefficiency and waste

that unnecessarily costs taxpayers millions of dollars and forces them

to pay for the water use of everyone else on the system.” Moreover,

she continued, “The state’s conservation plan deliberately bypasses

many proven conservation techniques other Western states adopted two decades

ago.”

Water experts who were interviewed explained that the problem is compounded

by the population’s careless ways: Utahns waste up to 25 to 50 percent

of all the water they use outside by relying on automatic sprinkling systems,

which tend to over water by about 44 percent; by planting water-consuming

Kentucky bluegrass lawn, rather than native, drought-resistant grasses;

and by growing gardens of water-needy types of vegetation rather than

native shrubs and flowers.

|

Solutions to the problem are available, even obvious, argued water managers, but no one seems capable of addressing the problems directly. For example, Utahns pay among the lowest water rates in the country because real costs are hidden in federal, sales, and property taxes. As a result, monthly water bills reflect only one-half of actual cost. “Incentives should be provided for those who conserve water instead of rewarding those who waste it,” argued Zack Frankel BS’91, director of the Utah Rivers Council.

The message of the KUER program was that the water shortage threat is permanent and will require a change in Westerners’ lifelong cultural attitudes and water usage practices.

Utah is a desert. Get used to it.

It could be argued that if Powell’s advice had been heeded,

Utah and the rest of the West would be in a better position to face these

problems today. At the time, however, Powell’s ideas were either

given scant attention or were spurned.“Science,” writes Stegner,

“had gone down before credulity, superstition, habit.”

Lessons were learned, belatedly, during periods of drought in the late

19th century and again in the 20th, especially during the Dust Bowl era

of the 1930s, which led to the adoption of many of Powell’s suggestions

regarding land classification, unfenced ranges, irrigation regulation,

and development of hydroelectric power. However, in 1953, just before

Hundredth Meridian was published, Stegner remarked that the myth-makers

were still at work, holding sway with public opinion.

“The private interests that [Powell] feared might monopolize land

or water in the West are still there, still trying to do just that,”

writes Stegner. “And the scientific solutions to Western problems

are still fouled up by Gilpins, by the double-talk of Western members

of Congress, by political pressures from oil or stock or power or land

or water companies, by the obfuscations of press agents and the urgings

of lobbyists.”

While the obfuscations will most likely continue, one thing is clear:

Powell was a visionary, a thinker ahead of his time. Contemporary policymakers

would do well to follow his example. Notes Stegner: “Instead of preaching

unlimited supply and unrestrained exploitation, [Powell] would preach

conservation of an already partly gutted continent and planning for the

development of what remained.”

—Linda Marion BFA’67 MFA’71 is managing editor of Continuum.