VOL.10 NO. 4 SPRING 2001

KEEPER

KEEPER

OF THE

WORD

by

Elise Lazar

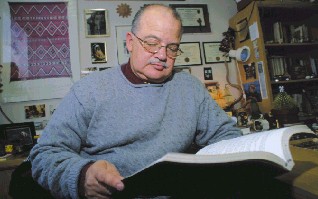

Photo by Andrew Gillman

To enter Mauricio Mixco’s office is to be suffused with delight. There are treasures everywhere: artifacts covering his desk and bookshelves, portraits, paintings, and newspaper clippings adorning his wall, a handcarved, primitively strung bow and arrow hanging from the ceiling, a jute basket resting in a corner. The abundance of memorabilia attests to a life rich in experiences. Yet the artifacts, as fascinating as they may be, are merely sidebars to Mixco’s real story—that of a lifetime of adventure in the pursuit and capture of a potential casualty of modern times: the endangered language.

An endangered language is one that is spoken by a diminishing number of people and that, more significantly, is not being taught to children, mostly as a result of attrition or scattering of the population, natural or enforced assimilation, or war.

Concepts such as endangered species and the loss of biodiversity have become disturbingly familiar to us. But the loss of the diversity of language is equally distressing.

The number of languages already lost and the projection of further extinc tions are alarming. In Australia, aboriginal peoples spoke approximately 260 languages at the time of their first contact with Europeans in the 1700s. Currently, only about 20 are still being used by a significant number of people; the rest are extinct. The United States and Canada, where it is estimated that more than 700 native languages were spoken at the time of Columbus, now have fewer than 200. According to Science magazine, “The world’s six billion people speak approximately 6,000 to 7,000 languages, and most experts expect that at least half—and perhaps 90 percent—will disappear in the 21st century.” It is predicted that before long, everyone will be speaking English, Mandarin, or Spanish.

Small wonder that experts such as Mixco, professor of anthropological linguistics at the U, are scurrying to identify endangered languages before they are lost. A subcommittee of the Linguistic Society of America ranks the degree of danger faced by such languages. Just as triage is used by emergency-room doctors to rank patients, the subcommittee prioritizes languages in order to Mauricio Mixco and the rescue of endangered languages mine those that require the most immediate research. Linguists then go out into the field in an attempt to preserve the language through recordings, documentation, and analysis.

Mixco is well suited to such work. Born in El Salvador, he moved early on to California, where he served as translator for his mother, a garment worker. “I had to go back and forth between two cultures,” he explains, and, as a result, unlike many children of refugees who assimilate into their new culture and disdain their native tongue, Mixco maintained his facility in both English and Spanish. He also developed an ease for learning other languages.

Mixco excelled in school, and after a semester at New Mexico State University, he transferred to the University of California, Berkeley. During those college years, his career path took shape. He taught Spanish to Peace Corps volunteers, spent two weeks at an Apache reservation (where he discovered an ability to imitate the language), and took his first linguistics course. Mixco was hooked. He received his B.A. and Ph.D. at Berkeley, specializing in Native American linguistics, a field in which native languages are described scientifically, their historical roots traced in order to recover knowledge about native prehistory.

While working towards his doctorate, Mixco accepted a summer field-work position for graduate students that entailed documenting endangered languages. It was a defining moment when he drove south to Mexico—the beginning of a professional commitment and a lifetime of adventure.

Short and stocky, Mixco may not be central casting’s Indiana Jones. But for years, from 1965 to 1993, he took off for two or three months at a time for high adventure. He studied the Mandan language in North Dakota for five years, and spent many more years doing field research in the Baja Peninsula of Mexico. At the beginning, he says, it was “naïveté” and a grant from the Survey of California Indian Languages that enticed him to drive over mountain passes (“all dirt, sometimes mud”) to seek the small, isolated villages of hardscrabble existences and little-known languages. But as trust was developed and stories were told, the relationships and the fascination with the culture, as well as the academic thrill of linguistic discovery, deepened Mixco’s commitment.

During this time he met 80-year-old Rufino Ochurte, whom Mixco describes as “one of the most interest ing people I have met in my life.” Ochurte lived in the Arroyo del Leon region, some one hundred miles south of the United States border, and was one of only 12 people who spoke the now-extinct Kiliwa language. Based on extensive interviews conducted over several years, Mixco wrote Kiliwa Texts, with the subtitle, “When I Have Donned My Crest of Stars,” a quote taken from an interview with Ochurte (see side bar).

Kiliwa Texts contains stories that are invaluable both for their thorough linguistic analysis of the language and for their documentation of the beliefs, traditions, and social and practical aspects of the culture. “With Ochurte’s death,” Mixco says, “his world, and the world of his ancestors, died with him, to be preserved only in these pages.” There are myths and legends relating to creation, migration, war, constellations of the stars, and death, as well as ethnographic texts describing such aspects of the culture as the mourning ceremony, dances, games, foods, advice to youth, crime and punishment, and personal narratives.

“Imagine,” Mixco exclaims, “I was able to rescue stories that are unique to this little group of people. Even as fragmentary as the stories are, it’s like meeting Homer’s great, great grand-child and piecing together The Iliad from what the grandchild remembers. It’s just enough to give me a sense of ‘Wow, there’s a whole universe here.’ It’s tremendously satisfying. If that’s all I did with my life, I’d feel very good about it.”

Surrounded as he is with evidence of a life well spent and rich in memories, Mixco should feel satisfied. His legacy includes several publications, including three books in the University Press’ “Anthropological Papers” series, warm relationships, and the preservation of a now-extinct culture. As Ochurte put it, “[W]hat I’ve said and the way I have been will remain in this land.”

—Elise Lazar, who wrote about Charles Dibble and The Florentine Codex in the Fall 2000 Continuum, is director of marketing for the Department of Theatre and a freelance writer.

|

|

|

Continuum

Home Page - University of Utah

Home Page - Alumni

Association Home Page

Copyright 2001 by The University of Utah Alumni Association |