Vol. 15 No. 2 |

Fall 2005 |

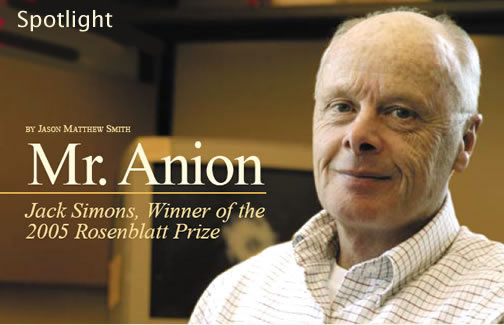

Photo by Lance W. Duffin

But the call turned out to be about news Simons wasn’t quite expecting: He’d been selected as the winner of the 2005 Rosenblatt Prize, the University’s highest honor for faculty, a not-so-subtle nod from your peers that you’ve been successful in handling the academic holy trinity of research, teaching, and administrative duties.

Not bad for a Midwestern boy who used to mix chemicals in his family’s basement, coming perilously close to burning the house down a few times. Simons was born and raised in Girard, Ohio, a suburb of Youngstown near the Pennsylvania border, where he kept his intellectual curiosity under wraps. In that part of Ohio, it was assumed that you would go to work in the mill or the mine. Few attended a university. But Simons had a secret. He says, “In my heart I was curious about science, how the world works.”

Simons did go to college—at the Case Institute of Technology in Cleveland, and to grad school at the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Next came post-doctoral work at MIT before he joined the U of U Department of Chemistry in 1971. He was awarded Alfred P. Sloan, Guggenheim, and other research fellowships, as well as an International Academy of Quantum Molecular Sciences Medal (considered the “Oscar” of theoretical chemistry). He also authored a widely used organic chemistry textbook, and published enough papers to fi ll the back seat of a Cadillac.

Simons’s work has centered on anions, or negatively charged molecular ions, and his groundbreaking efforts have earned him the moniker “Mr. Anion.” Any gathering of chemists will tell you about Mr. Anion and how his theoretical models have enabled chemists to more accurately understand or predict what happens at the molecular level. Think of a sunburn at high altitudes: His work helped researchers understand why a sunburn sets off a chain reaction that ravages DNA and causes cancer.

Yet he chalks up the disciplinary fame to the natural progression of a scientist’s career. “You tend to go into [one] area and become czar.”

Peter Armentrout, chemistry department chair and Simons’ colleague, isn’t a bit surprised that Simons walked away with this year’s Rosenblatt Prize. “Jack has the ability to interact with just about everybody,” he says, “and he can relate difficult concepts in an intelligent and educational way.”

Because he can break down complicated ideas so well, Simons has been a popular professor in the department, influencing an entire generation of scientists. On any given day, you’ll find him gliding through a maze of cubicles outside his office to look in on young chemists and their work, asking, “Whatcha got?” And that’s his favorite part of the job. “I enjoy getting to know these people,” he says, “How they think, how they are as human beings.”

That’s because he sees a little of himself in these scientists who are just getting their careers off the ground, so fresh from experiments in their own basements.

—Jason Matthew Smith is editor of Continuum.