|

||

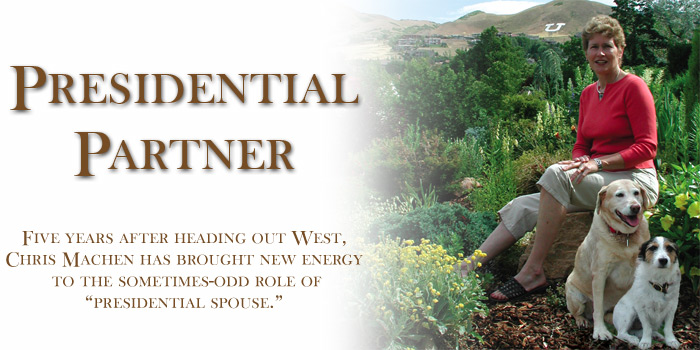

Five years ago, Bernie and Chris Machen hosted a summer barbecue at the Rosenblatt House, the president's residence, for the University cabinet and deans. They had just arrived in Utah and wanted an informal way to get to know the people they'd be working with closely. "We said 'casual' on the invitation," remembers Chris Machen, "and some people came in coats and ties. I was in linen shorts and Bernie had on khakis and a golf shirt. People said to us, 'Oh, you really meant it?'" Yep, they really meant it. And the barbecue established more than the Machens' informal dress code. It introduced Chris Machen as an informal, and hard-working, University advocate, a new kind of presidential partner. And as a true, if previously displaced, Westerner. "I had always wanted to live in the West," says Machen, a horsewoman from the Midwest, "but I never thought I'd have the chance." Since that barbecue, Machen's reputation has grown--in all the right ways. She has walked into the strange role of "presidential spouse" and redefined and reinvigorated it, perhaps not by design but by extension of her own personality. "She's a do-er," says Barb Snyder, vice president for student affairs. "She's not content to sit back." Indeed, Machen has served on the Fine Arts Advisory Board, the Red Butte Garden Advisory Board, the Coalition for Utah's Future, the Utah Women's Forum, the U of U Hospital Foundation board, the Bennion Center Advisory Board, the President's Commission on the Status of Women, and the National Ability Center Board—among others. She hosts dozens of events for speakers and groups at the Rosenblatt House every year and attends numerous dinners, lectures, award presentations, and panels across campus. As Lorna Matheson, former Board of Trustees member and Alumni Association president, says, "She's the best unpaid employee the state of Utah has." Matheson's description is apt. Nationally there is growing recognition of the substantial work done by presidential partners. A recent article in The Chronicle of Higher Education discussed a study by the Council of Independent Colleges showing that 23 percent of the members' spouses received some level of compensation for their work. Machen points out, "I'm not Hillary Clinton—though I like her. I never wanted to be in the cabinet." But her genuine interest in university life and university people, her approachability, and her energy have made her a natural contributor to campus and off-campus groups, and have changed the perception of her "role." Smart, funny, and down-to-earth, "she's become more comfortable as the role has become more active and less social," says Snyder. Born and raised in St. Louis—in the kind of neighborhood where, she says, "you could make your hopscotch marks and nobody would erase them"—Machen is a nursing graduate of St. Louis University. She and Bernie were married after graduation and she immediately began work in a newborn intensive care unit--and stayed in neonatology for 28 years. But only one of those years was spent in St. Louis. Machen would eventually find herself working in South Carolina, Iowa, Maryland, North Carolina, and Michigan, as Bernie's career in academic dentistry took them to different schools around the country. Machen easily found work in every state. "If you have a warm body and a beating heart, you can get a job," she says of nursing. Adjusting to the relocations was a little more challenging, however. When the young couple made their first move, to Charleston, South Carolina, it was the first time Machen had lived outside of St. Louis and away from her family--Mom, protective Dad, and two sisters. "Bernie had moved a lot growing up, but I hadn't at all. I remember calling my mom and saying, 'I have the Tupperware lady in the closet. She's the only one who'll talk to me.'" Still, the isolation didn't last. "We met all kinds of people," she says, "and had new experiences. I remember that we won a boat--and we never win anything—and we were able to take it out into the harbor. That was great." An early seeker of silver linings, Machen's optimism and outgoing nature have remained, traits essential to frequent movers. After two years in South Carolina, the Machens spent three years in Iowa, where Bernie got his doctorate at the University of Iowa and Chris worked again in pediatric nursing and as a clinical instructor at the university's nursing school. Then, "the army got us," and the family, which now included oldest son, Lee, moved to Fort Mead, Maryland, for two years, where son Michael was born. Then came 15 years in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, which, says Machen, "was wonderful--fleas, humidity, and all. That was where we raised our family." Their youngest child, Maggie, was born there. While Bernie was a professor and then associate dean at the University of North Carolina's School of Dentistry, Chris worked at the university hospital. And it was in Chapel Hill that she began to ride horses. "I started the same way everyone does—I kept getting hurt," she says.

Indeed, mother and daughter continued to do 4-H together when the family moved again, to Ann Arbor, Michigan, where Machen admits she needed the comfort of those big, furry animals. "Ann Arbor was sort of a hard one," she says. "It took a long time to feel at home." Bernie, who eventually became provost at the University of Michigan, had "one hard job," and Machen herself embarked on a new field, pediatric home health. "I got to see how babies do when they leave the ICU," she says, a job that requires a warm touch and an ability to relate to almost any family—qualities Machen's friends still attribute to her. After nine years in Ann Arbor, "Bernie was ready to be president," Machen says, and she found herself, finally, heading out West. She says she felt the difference in Utah almost immediately—above and beyond the ready acceptance of Hank, the horse she brought with her. For one, "people have been overwhelmingly kind and thoughtful," she says. "There are the most generous, giving people here than anywhere we've been. You should have seen the flowers and cards I got when Hank died [in 2002?]." For another, being president is a completely different role—for both president and partner—than any other academic job. "In Michigan, Bernie was provost, which is a position only university people care about," Machen points out. "The community doesn't care. So I really wasn't that involved." Thus, the expectations that met this longtime nurse-suddenly-turned-public hostess were different, too. "I was overwhelmed at the beginning," Machen admits, "and felt a little invisible sometimes. I didn't know who anyone was, so my brain was on extra firings at every event." True to form, however, Machen quickly made friends and got involved at the U. "Whether you're faculty, staff, part-time, whatever, she has a way of making you feel welcomed and recognized," says Phyllis Haskell, dean of the College of Fine Arts. "There's not an ounce of her that is elitist. She's very present when you're with her." In fact, when Haskell approached Machen about serving on the Fine Arts Advisory Board, Machen laughed. "I told Phyllis, 'I like Garth Brooks. I do 4-H. What would I do on the board?' But it's been so fun, and a real continuing education course." Machen says some of her favorite times at the U have been spent meeting "fascinating people"--whether it's through the Middle East Center's lecture series or the 2002 Olympic Winter Games. "We came to Utah in part because we knew the Olympics would be here," she says. "And it was wonderful. Bernie lost a little more hair, but it was wonderful." And over time, she says, she has seen her own role expand. "I think that part of my role is university-community relations, to get to know people who don't know the U. I started realizing that I'm in a unique position—I'm all over campus. Everyone else is in their own little realm. So what's become fun is to link people up, to make connections." For example, Snyder remembers, "About a year ago, Chris read about the new president of the Relief Society of the Church [of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints]. So she got together a group of campus and Relief Society representatives to talk about issues we share. They've met a couple of times to discuss things that are important to students and to the Church. Chris just seizes the moment, and she cares deeply." Machen also serves on the board of the Western Folklife Center, the Elko, Nevada-based host of the National Cowboy Poetry Gathering. Machen, a 30-year subscriber to Western Horseman magazine, first heard of the gathering when she lived in North Carolina. "She's really got an infectious enthusiasm," says Hal Cannon, the center's director. "It's hard to be in a position like hers and still be an open, enthused, interested person. It'd be easy to close down, because everyone wants her or her husband's ear. But then, she's not your typical power person." Well, no. Her power points? She likes gardening at her home in Heber. She likes riding a motorcycle for two with Bernie. She likes audio books and bluegrass music and the women-only movie club she belongs to, Flix Chix. She likes rural areas and small towns. She loves her new horse, Zippy, but has renamed him "Zip" because "'Zippy' is dumb." No matter what the Machens' next move will be--and "all

I can say about that is that these jobs are weird," she says—Machen's

genuine, vibrant nature will no doubt prevail. "I've never been bored

in my life," she points out, "especially when I'm alone." --Theresa Desmond is editor of Continuum. |

||

But learning to ride and being in 4-H with her daughter were turning points. "I like the whole atmosphere around horses," Machen says. "I like to go to the barn, I like to groom the horse, I like to talk to my friends. They don't care who I am. And the barn is a total distraction. You have to pay total attention while you're there." Plus, she says, "for me, there's something about that big, furry animal--those thousand pounds of fur will always be there for you."

But learning to ride and being in 4-H with her daughter were turning points. "I like the whole atmosphere around horses," Machen says. "I like to go to the barn, I like to groom the horse, I like to talk to my friends. They don't care who I am. And the barn is a total distraction. You have to pay total attention while you're there." Plus, she says, "for me, there's something about that big, furry animal--those thousand pounds of fur will always be there for you."