VOL.10 NO. 2 THE MAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF UTAH FALL 2000

Every Student A Politician

For Hinckley Institute of Politics founder Robert H. Hinckley, it was a rally cry. For student interns in Washington, D.C., it's reality.

by Anne Palmer Peterson

"One thing we always tell students before they go back there is, 'Open your eyes and ears; don't just go to work. Get out, look around, read the papers, go to Congressional hearings, ask your employer for a day off here and there to do some important travel on the weekends. Go to museums. Don't do anything you could do in Salt Lake City. Don't go to movies. Don't sleep. Just go take it in.'"

Each year since 1966, as many

as 120 University of Utah students in the District of Columbia board the

subway every morning in order to staff copiers, format documents, and

run errands with a reverence and devotion that makes their service seem

almost a civic sacrament. The fact of the matter is, "a lot of what

the students do is donkey work," according to Ted Wilson BS'64, who

chucked his job as mayor of Salt Lake City midterm to head the University's

political institute. "Precinct work," arranged by the Hinckley

Institute of Politics, helps teach students to become informed participants

in the American political system. Answering phones and writing correspondence

some of the time hasn't tempered students' eagerness to enter the fray.

Judging

by the stiff competition for the privilege and that roughly 3,500 internships

have been served so far, working inside the Beltway seems a fitting complement

to a Utah undergraduate education. Serving as interns for justices, lobbyists,

and members of Congress, with nonprofit administrators, or for network

broadcasters seems to resonate with Utahns' sensibilities.

Judging

by the stiff competition for the privilege and that roughly 3,500 internships

have been served so far, working inside the Beltway seems a fitting complement

to a Utah undergraduate education. Serving as interns for justices, lobbyists,

and members of Congress, with nonprofit administrators, or for network

broadcasters seems to resonate with Utahns' sensibilities.

"Is it a coincidence

that the Hinckley Institute of Politics and the Bennion [Community Service]

Center both flourish at the U, when other institutions have trouble achieving

the same success on a steady and continuing basis?" postulates former

Institute director R.J. Snow BA'62 MA'64. "I think Utah values are

better defined and maintained than elsewhere, and both the Hinckley and

Bennion ideals have always had support at the U, even before there were

such excellent opportunities for students to find ways to express themselves."

After all, patriotism is part

of the conscience many students bring to the U. For some, the regard for

their country has been inaugurated at church or school and embellished

at small-town Independence Day parades and rodeos, high school community-service

projects, or Scouts. Freedom of religion has its basis in politics, as

well—a lesson understood by leaders and followers of many faiths,

whether Protestant, LDS, or Jew. Among the U student body are many with

convictions of another kind: a belief that a college education ought to

avail students of life away from home. Students adhering to either ideology

are encouraged by the Hinckley Institute of Politics to apply.

Robert H. Hinckley, founder

of the Institute, wanted the lure of politics to be irresistible so that

the "young, best minds" could be taught to appreciate the responsibilities—as

well as the privileges—of citizenship. After years in government—as

a state legislator and mayor of Mt. Pleasant, with the Civilian Conservation

Corps, Works Progress Administration, Federal Emergency Relief Administration,

Civil Aeronautics Authority, and as Assistant Secretary of Commerce for

Aviation—Hinckley became increasingly concerned about public attitudes

toward politics. A former regent of the University, he came to believe

that one of the University's roles ought to be in preparing students for

political careers.

|

|

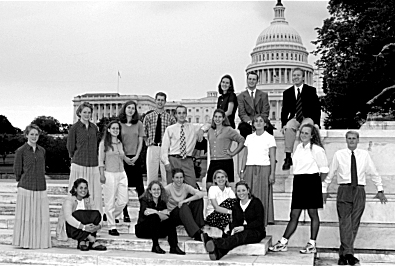

Fall 1999 interns: Top row (l-r): Jaclyn Thomas, Peter Watkins, Scott Bauman. Middle row (l-r): Amy Hyde, Jessica Shulsen, Jenny Nicholas, Dan England, Joe Boud, Emily Henderson, Jodi Hinckley, Kelly Wessels, Spencer Wixom. Front row: (l-r): Jane Gardiner, Mindy McArthur, Jill Horton, Jill Mathis, Meagan Marriott. |

Upon retiring to Utah, his

sense of the need for a political institute grew urgent, according to

his biographer and former Hinckley Institute Associate Director Bae Bishop

Gardner ex'49. Before determining the Institute should be founded at the

U of U, Hinckley studied models at Yale University to learn about fellowships

for hosting public leaders on campus: Grinnell College in Iowa; the proposed

John F. Kennedy School of Government at Harvard; the Maxwell School of

Government at Syracuse University in New York; and the Eagleton Institute

at Rutgers University in New Jersey. His research convinced him to focus

on education, students, and participation as means of making democracy

make sense again.

"After years…in

public service and in the broadcasting industry, I have taken it upon

myself to go up and down the land preaching the gospel of politics and

political involvement…[and] patriotism—that old-time religion…,"

wrote Hinckley. A prosaic document drafted at the founding of the Institute

decries "the tragedy that there is a national pastime of belittling

and downgrading politics and politicians" and pledges to "inculcate

a wholesome respect for politicians in coming generations." As Snow

points out, the Institute was the beneficiary of Hinckley's convincing

others to put their money behind it—his own family (who willingly

watched much of their inheritance shift to the Institute), Hinckley's

ABC-TV co-founder Edward John Noble, Marriner and George Eccles, Joseph

Quinney, and, later, Rocco Siciliano. From 1975 to 1985, Snow, the University's

vice president for university relations, also directed the Institute.

Gardner, assistant director, ran the day-to-day affairs and coordinated

internships.

The Institute's $8 million

endowment, and the efforts of founding director and political science

professor J.D. Williams, enabled the first interns in the summer quarter

of 1966 to serve in U.S. Congressional offices and to be paid while earning

college credit. "In medical school, internships provide on-the-job

learning so that young people can take their academic training and try

it in an actual work situation. That was our fundamental logic, and we

were fortunate the U.S. Congressional delegation was so cooperative,"

says Williams.

Today students are also placed

at prestigious federal institutions, nonprofit groups, and political think

tanks. What's more, the Institute subsidizes convenient, comfortable accommodations

just outside the nation's capital in Alexandria, Virginia's Oakwood Apartments.

Interns pay $125 per month. Benefactors also have enabled the Institute

to provide stipends for interns of $600 per month, making the opportunity

to go to Washington affordable to a wider range of students. Few, if any

other, college internship programs in Washington provide students all

three resources: jobs, money, and housing.

Wilson says he frequently

takes calls from parents of BYU students asking, "If my child transfers

to the U, can she apply for a Washington, D.C., internship?"

Students live in connecting,

furnished apartment suites at a corporate housing complex that includes

such suburban amenities as swimming, tennis, and sand volleyball. On a

free shuttlebus that takes residents to and from the Metro line, the University's

interns spend time outside of work together. They also get to know one

another at potluck dinners and organized sight-seeing trips to destinations

such as Gettysburg, Mt. Vernon, Williamsburg, Boston, New York, Monticello,

Bull Run, and Baltimore.

For many, it is the first

professional experience of their lives. And culturally, it will be one

of the richest, according to Wilson.

"One thing we always

tell students before they go back there is, 'Open your eyes and ears;

don't just go to work. Get out, look around, read the papers, go to Congressional

hearings, ask your employer for a day off here and there to do some important

travel on the weekends. Go to museums. Don't do anything you could do

in Salt Lake City. Don't go to movies. Don't sleep. Just go take it in.'"

They're prone to heed the advice.

"Washington, D.C., is

a city that runs at a far different pace than what I'm used to. I recognized

the importance of being well informed, so I tried every day to read The

Washington Post, The Times of London, The New York Times, and The

Los Angeles Times. They were provided at my work, and I'd skim all

of them every morning," says Spencer Wixom. Great work, if you can

get it, especially for a college student. Wixom was a fall 1999 intern

to the U.S. Supreme Court who gave tours and researched the history of

paintings from the National Gallery of Art and the National Gallery of

American Art displayed in the justices' chambers. "I enjoy taking

an active part not only in politics but in the celebration of American

tradition and American freedoms—just to understand the nation we

live in and how it functions politically, economically, and socially,"

says the senior double major in engineering and business. Visual art,

it turned out, was the cultural asset he valued most in Washington, D.C.

Attorney Kirk Jowers BA'92, a former intern and recipient of a $28,000 Harry S. Truman scholarship administered by the Hinckley Institute of Politics, is an on-site advisor to the U's Washington interns and associate general counsel for the Advisory Commission on Electronic Commerce. Jowers raves about the variety and quality of internships available. "If you want to be a journalist, or a lawyer, or a public official, the Institute has places where you get paid to learn about the work you'll be doing. Even if you want to go into business, you still ought to understand that business answers to government, and you need to know how it works in order to create a business or lobby for more advantageous terms. No matter what kind of tasks interns do back here, understanding how government works enhances their ability to participate," he reiterates.

|

|

Former intern Kirk Jowers BA'92 (l.) visits with fall 1999 interns Jason VandenAkker and Jill Mathis. Photo by Brad Nelson |

"These people wouldn't

have you there if you were going to replace the CEO or the chief of staff,"

Wilson admits. "Your job is to help them." Still, the Institute

will intervene if interns report being saddled primarily with menial tasks.

"We have to watch that day and night. And we tell students, 'If you

find yourself tethered to the copy machine, you let us know, because we

want this to be a substantive experience for you.' But writing letters

and tracing bills can be an important learning experience," adds

Wilson, who assumed the Institute's helm 15 years ago.

Many Hinckley interns wind

up with Potomac fever: an infectious desire to live and work in the capital

of the United States. "The people I worked with at the Supreme Court

would say, 'Once you get Washington in your blood, you never give it up,'"

states Amy Richins Oliver BS'95, who recently landed a job with a District

of Columbia law firm. She didn't realize that the opportunity she'd had

to work at the Court during college was such a coup—until the dean

of the law school at Harvard pointed it out to her and the rest of the

class of 2000.

Jill Mathis, intern for Congressman

Jim Hansen, is a U student without much background in political science

but who wanted the experience of living back East. Friends who had previously

interned encouraged her to apply. Mathis wants to teach children or possibly

go into social work. "I'm not interested in staying in politics,

but I do want to be more up on current events, particularly issues that

affect children," she says. The day before, she had attended a press

conference advocating reforms to laws that potentially undermine the stability

of immigrant families while members are held for deportation hearings

based on so-called "secret evidence." "Taking people on

tours of the Capitol gets you interested in issues, and about how government

works," she says.

Former ASUU President Ben

McAdams BA'00 is proof of what he preaches when he says a Washington,

D.C., internship "opens doors that you never even knew existed."

He was an electrical engineering major with only a fleeting interest in

politics when he gained a University internship in the White House. "I

was fascinated with the White House press corps, so I studied the press

and developed skills to work with the media," McAdams explains. Following

his internship, he was selected by the president's Advance Team to orchestrate

media logistics for some of President and Mrs. Clinton's domestic and

international travel, including Mrs. Clinton's visit with ethnic Albanians

and the Macedonian people who took them in. McAdams has continued in that

role for the past two years and says he intends to pursue "some kind

of public service" after law school at Columbia University.

The only thing more inspiring,

as far as leaders of the Hinckley Institute of Politics are concerned,

is former interns running for elected office. That happens all the time,

too. They include former speaker of the Utah House of Representatives

Rob Bishop BS'74, Senator Fred Finlinson BS'67 JD'69, Frank Pignanelli

BS'81 JD'84, who served as minority leader of the House, Randy Horiuchi

BS'75, Jim Bradley BS'84, Jim Davis BS'72, and Enid Greene BS'80. Greene

became the student who obtained the highest elective office of Hinckley

interns when she was elected to the United States Congress from Utah's

second district. The name of former intern Donald Dunn BS'93 is set to

appear on the Third U.S. Congressional District ballot in the state of

Utah this fall.

Would they have done it without having served internships? Hard telling. The ideals fundamental to politics are also inherent to education. Both are seductive forces.

—Anne Palmer Peterson MPA'00 is former editor of Continuum. She is an academic program manager for educational administration in Academic Outreach and Continuing Education at the University.

Continuum Home Page - University of Utah Home Page - Alumni Association Home Page

Questions, Comments - Table of Contents

Copyright 2000 by The University of Utah Alumni Association