VOL.10 NO. 2 THE MAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF UTAH FALL 2000

Bone Digger Utah Museum of Natural History paleontologist Scott Sampson scours the world for dinosaur remains.

by Ann

Floor

Photos By Dennis Haynes

Scott

Sampson has been interested in dinosaurs since he was five years old.

"Paleontology was one of the first words I learned to spell,

and I guess I never quite grew up," he says with great enthusiasm.

"I've spent my entire adult life travelling around the world digging

up bones, and I just keep hunting for more." Indeed, the Utah Museum

of Natural History's new paleontologist, who arrived at the U one year

ago, is generating new excitement in the science of fossil research.

Scott

Sampson has been interested in dinosaurs since he was five years old.

"Paleontology was one of the first words I learned to spell,

and I guess I never quite grew up," he says with great enthusiasm.

"I've spent my entire adult life travelling around the world digging

up bones, and I just keep hunting for more." Indeed, the Utah Museum

of Natural History's new paleontologist, who arrived at the U one year

ago, is generating new excitement in the science of fossil research.

Take Sampson's most recent

discovery, made during the summer of 1999 when he was in Madagascar. It

was his fourth trip and he thought most of the big dinosaurs had been

found. But walking through the hills one day, he literally stumbled across

the remains of what looks to be a brand-new, previously unknown species

of carnivorous dinosaur. Sampson's previous field seasons in Madagascar

had produced the fossil bird Rahonavis, a critical missing link between

dinosaurs and birds, and a spectacular skull of the large theropod (carnivorous)

dinosaur Majungatholus. And he has made other discoveries in Zimbabwe

and South Africa, Southern-Hemisphere sites especially rich in undiscovered

fossils, as they have not been explored as much as sites in the Northern

Hemisphere.

But as Sampson says, "It's

not Indiana Jones all the time. After the first couple of days working

in 100-degree temperatures, living in a tent with no running water and

lots of bugs, the romance wears off. Yet walking around a corner and never

knowing if you're going to find something that no human being's ever seen

before—that keeps you going."

Sampson's work in this hemisphere has yielded some extraordinary finds as well. He described and named two new forms from the Late Cretaceous period (circa 75 million years ago) in Montana. One he named Einiosaurus, which means "buffalo lizard" from the Blackfoot Indian word eini, meaning buffalo; the other was coined Achelousaurus after a Greek river god named Achelous who could change his shape at will.

Last summer, Sampson was

offered a dual position as curator of vertebrate paleontology at the Utah

Museum of Natural History and assistant professor in the Department of

Geology and Geophysics at the U. Sampson, who was born and raised in Vancouver,

British Columbia, and worked at the American Museum of Natural History

in New York City, likes wearing both hats. "I waited several years

for the right position to pop up and couldn't have written a better job

description for myself," he says.

The unique arrangement will

enable him to bring the science of paleontology to a broad range of graduate

and undergraduate students through his teaching, while maintaining his

role as museum curator—finding fossils, digging them up, bringing

them back to the museum, publishing papers on what is found, and interpreting

the findings for the public.

|

|

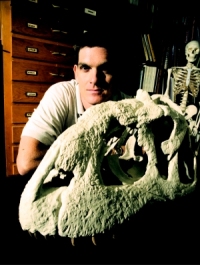

Scott Sampson and the skull of Majungatholus |

Ann Hanniball, the museum's

assistant director for community relations, has worked with Sampson for

the past year. "Scott has enormous energy and is endlessly curious,"

she says. "He thinks globally and understands how paleontology connects

to a number of other things. He really has an ecumenical point of view."

As Sampson notes, "Paleontology can be a bridge of understanding between past and present life-forms. And dinosaurs provide an opportunity to access virtually any area of science." Next spring semester, he brings this philosophy to a brand-new course aimed at all undergraduates. The course, "The World of Dinosaurs," will use the study of dinosaurs as a vehicle to teach the nature and process of science. Discussions will go well beyond dinosaurs to include such topics as plate tectonics and ancient climates.

Utah has a strong reputation

as an important center for dinosaur research, and the potential to find

new animals here is great. Indeed, recently a technician from the University's

geology department made a thrilling discovery when he stumbled across

what appears to be the first Tyrannosaurus rex found in Utah. A

few bones have been collected, and the hope is that most of the animal

remains to be unearthed. If so, it will be excavated and studied to see

if it truly represents Tyrannosaurus rex or perhaps some other

species of Tyrannosaurus.

In Utah, the Cleveland-Lloyd

dinosaur quarry (near Castle Dale) and Dinosaur National Monument (adjacent

to Vernal) are important sites, but there are some areas in southern Utah

that are likely to cause a lot of excitement as well. "We were down

in Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument several weeks ago talking

with the monument staff, and in the space of just four hours of wandering

around, we found three new kinds of extinct animals, including two new

dinosaurs," exclaims Sampson.

Discovering dinosaur fossils is much easier in badlands where rocks are exposed than in grassy fields. Bones can range in color from white to black, with everything in between. And bone is like wood—it has a grain to it. Rocks have a different kind of grain or cross section. "You have to get an eye for it," says Sampson. "You have to be able to separate the rocks from the bones, and sometimes it takes a while to see the difference. But once you know what color and shape to look for, then you can really start to pick things out."

|

|

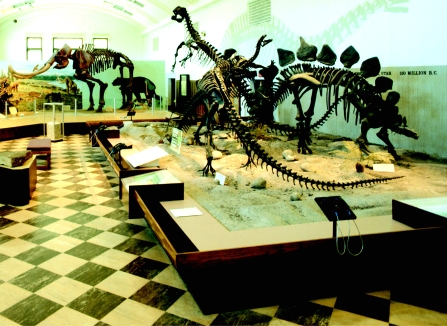

Main exhibit hall, Utah Museum of Natural History |

Along with shovels, picks,

and brushes, high-tech tools are now used. Global positioning system (GPS)

units map the exact location of a site to make it easier to re-find, and

a recent technique has successfully employed detection of radioactivity

to locate fossils still interred within the sediments.

When a bone is discovered, it's not just picked up off the ground. It's

usually fragile and could break into pieces, so it first needs to be stabilized.

A solution of glue thinned with acetone is squirted on the fossil to harden

it. From there, it's wrapped with plaster and burlap for protection. These

plaster jackets, made on-site by members of the field team, provide protection

for the fossil during its transport. Together with their ancient contents,

the jackets can be as small and light as a pencil or as massive as a multi-ton

truck, so moving them can be a challenge.

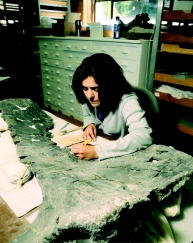

Once the specimen is safely

back at the museum, the fossils are prepared in the Paleo Lab, a glass-walled

room that allows visitors to observe the students and volunteers at work.

Preparation involves removing the plaster jacket and the matrix, the rock-like

material found in the cavities of the fossil skeleton. One vertebra can

weigh over 50 pounds and take five or six weeks to prepare, so the preparation

can take months to complete, depending on the size of the animal.

|

|

Monica Castro BS'97 at work in the Paleo Lab |

The lab is managed by Mike

Getty, collections manager and chief preparator for the museum, who was

recruited last October from the Royal Tyrrell Museum of Paleontology in

Alberta. Getty oversees a volunteer staff of more than 40 people in the

Paleo Lab, and runs the field camp during fossil-hunting season. "I

like the fossils because they represent worlds that came before us,"

he says. "It's not often you can get in touch with something like

that."

Evolving technology is providing new possibilities in dinosaur research. Although DNA testing is not yet routinely used, it may be in the future. Recent discoveries have identified actual bio-molecules that have been preserved in fossils. The sheath on the claw of the fossil bird Rahonavis was found to include original organic material—preserved for 72 million years.

Scientists are beginning

to document the existence of these astounding soft tissue findings. The

journal Science recently announced the discovery of a fossilized

dinosaur heart from Montana. Because no one had really been looking for

remains of such soft tissue materials in the past, they weren't being

found. It's similar to the emergence of dinosaur egg discoveries. For

years, no one thought to look for baby dinosaurs or for dinosaur eggshells.

Then suddenly, after being recovered in a few places, they began to appear

all over the world.

The museum's collection of

Jurassic-age fossils is significant and includes both herbivorous and

carnivorous dinosaurs. But Utah undoubtedly has a plethora of fossils

that remain to be discovered, and the museum wants to bring some of those

specimens in, build up the collection, and do the related research and

education.

"So much of Utah remains

to be explored," says Sampson. "The fossils that are collected

and brought to the museum will be kept forevermore for people to enjoy."

Sampson says that many people don't realize that over 99 percent of all

the animals that have ever existed on this planet are now extinct. "Extinction

is not only common, it is the norm—the inevitable. The ironic thing

is that people use dinosaurs as the icon of failure. Yet dinosaurs were

the dominant land animals for about 150 million years, whereas humans

have been around for less than one million years." In short, we have

barely begun to tap into the prehistory of this state, and the museum

plans to fill major gaps in our knowledge.

Since 65 percent of Utah is

federally owned, most of the field research in the natural sciences is

being carried out on federally managed public lands. This means that the

museum and the federal government are partners in science. Testament to

this partnership is the fact that more than 75 percent of the museum's

million-plus objects and specimens, and 90 percent of its vertebrate fossils,

were recovered from public lands. The museum staff preserves these federal

specimens and provides scientific interpretations to the public through

exhibits at the museum as well as through outreach programs, such as the

travelling field crates—many filled with dinosaur-related objects—that

go to schools throughout Utah.

The museum has begun a capital campaign to raise money for a new natural history museum to be built on 14 acres in Research Park. If all goes well, groundbreaking will begin in 2004 or 2005 with completion two years later. A new museum would strengthen science for the entire state of Utah. As Sampson remarks, "There really isn't a large, full-scale natural history museum in this state. And if you look around, this state is nothing but natural history—it deserves to be well represented."

The Utah Museum of Natural History welcomes volunteers. For more information, call (801) 581-6927.

—Ann Floor, who last wrote about international conservation efforts at the U for Continuum (Fall 1998), is a freelance writer.

A Day at a Dig

We pull off the road in the

mountains west of Castle Dale in our camouflage truck (an Army Surplus

special) with its extra-wide cab. There's not an extra thing inside except

the boombox Mike Getty has rigged so he can play his tapes of a Canadian

band that sounds Irish.

Mike,

collections manager for the Utah Museum of Natural History, points to

a hill in the distance and tells us our quarry is somewhere up there in

the rock outcropping. There are five of us today. We walk through a flat

meadow and up a bone-dry streambed, then up the solid rock "tongue"

of the boulder-covered hillside to a plateau on top. The view is spectacular.

We walk across the plateau and start down the backside. Just over the

edge, below a huge boulder precariously perched on fragile support rocks,

is our site, which has been prepared for our visit. A four-foot-deep,

12-foot-long, and eight-foot-wide shelf has been carved out of the side

of the hill.

Mike,

collections manager for the Utah Museum of Natural History, points to

a hill in the distance and tells us our quarry is somewhere up there in

the rock outcropping. There are five of us today. We walk through a flat

meadow and up a bone-dry streambed, then up the solid rock "tongue"

of the boulder-covered hillside to a plateau on top. The view is spectacular.

We walk across the plateau and start down the backside. Just over the

edge, below a huge boulder precariously perched on fragile support rocks,

is our site, which has been prepared for our visit. A four-foot-deep,

12-foot-long, and eight-foot-wide shelf has been carved out of the side

of the hill.

Several shovels and a big

pickax stand in the shaded corner of the site. Mike takes our water bottles

and puts them with our lunches inside a shallow cave to keep them cool.

The sun is getting hot. We go to work.

First, we finish scraping

the loose dirt off the floor of the shelf with a shovel. Then we use our

awl and hammer to tap very carefully, taking off the earthen floor of

the shelf in tiny layers, one inch deep at a time. I sweep away the loose

dirt with a whisk broom.

As I'm working, I notice a

bright, almost electric, baby-blue chip below my hammer. This is unmistakably

a dinosaur bone. The clear blue is so different from the other, more muted

colors of dirt and stone.

Once I know it's a bone fragment,

I switch immediately to the one-inch soft paintbrush and carefully brush

around the bone. We are firmly instructed not to touch the fragments.

We continue the work all morning. By lunch, Mike has found a substantial

bone, and others have found fragments. We stop to eat, sitting in a line,

our backs against the dark cool wall of the earthen shelf. Some of us

take a few photos, then we go back to work.

By the end of the day, we

have made a second shallow "step" across the length of the shelf.

Mike asks us to carve moats around our findings to protect them from being

washed down the mountain in case it rains before he can come back. Each

little mound of rice- and pea-sized fossil flakes has its own plateau

with a protective trench around it to guide the water away.

By now I'm tired and dehydrated but excited, too. What if my hammer's tap is the first step toward a major find? We hike back up the hill and down the other side and back to the truck. Time to think about dinner.

—Ann Floor

Continuum Home Page - University of Utah Home Page - Alumni Association Home Page

Questions, Comments - Table of Contents

Copyright 2000 by The University of Utah Alumni Association