VOL.10 NO. 2 THE MAGAZINE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF UTAH FALL 2000

Aztec Civilization, Revealed

A tribute to Charles Dibbleby Elise Lazar

Photos By Brad Nelson

Images From Marriott Library Rare Books Division

The

auditorium was packed solid and noisy with students stepping over each

other to squeeze into makeshift seats in the aisles. Werner Herzog, an

international filmmaker and a Sterling McMurrin scholar, walked onto the

stage in Orson Spencer Hall and, simply with his presence, switched off

the noise. Dressed in faded jeans and a brown leather aviator jacket,

Herzog began. "I don't accept many invitations to speak. But when

I was invited to Salt Lake City, I knew immediately that I would come.

I have long wanted to make a pilgrimage here...to pay tribute to a man

by the name of Charles Dibble."

The

auditorium was packed solid and noisy with students stepping over each

other to squeeze into makeshift seats in the aisles. Werner Herzog, an

international filmmaker and a Sterling McMurrin scholar, walked onto the

stage in Orson Spencer Hall and, simply with his presence, switched off

the noise. Dressed in faded jeans and a brown leather aviator jacket,

Herzog began. "I don't accept many invitations to speak. But when

I was invited to Salt Lake City, I knew immediately that I would come.

I have long wanted to make a pilgrimage here...to pay tribute to a man

by the name of Charles Dibble."

There was a stir through the

audience and a heightened sense of collective interest. Herzog let the

name sink in and then continued. "Just as we all have a dictionary

and a Bible in our homes, we should all have a copy of The Florentine

Codex placed next to the other two books and regarded with the same

respect and esteem."

The Florentine Codex.

Even the name was intriguing. But never did I guess that the bait I had

just grabbed would lead me on a year's journey, one that ended on a gravel

road to meet Charles Dibble BA'36, the man who translated the codex and

provided one of the most important keys to our knowledge of the Aztec

civilization.

It is the story of two parallel collaborations, one 400 years ago involving a Franciscan priest, Bernardino de Sahagún, working with Mesoamerican natives, and the other, more recently, by Charles Dibble, his colleague Arthur Anderson, and the University of Utah, during a remarkable 30-year project.

The Man

Charles Dibble was born in Layton, Utah, in 1909. A year before graduating

in history from the University of Utah, he made a trip to Mexico that

ultimately defined his life as a Mesoamerican scholar. He received his

master's from the Universidad Nacional Autónomo de México

and began teaching at the U in 1939 while also returning to Mexico for

studies that led to his doctorate.

During his teaching career, which spanned 40 years, Dibble had great impact

on many students. Norma Mikkelsen BA'61, who was eventually to become

director of the U of U Press and work with Dibble in publishing The Florentine

Codex, first came to the University in 1948 as a sophomore. "I was

an English major, but to fulfill a social science requirement, I took

Dr. Dibble's class," she says. "During the course, I realized

that I had to be an anthropology major. That's how appealing and vital

he made his subject and how strong his influence was." He is the

only faculty member ever to be awarded the three most coveted awards of

the University: the Distinguished Research, Teaching, and Alumnus Awards.

Dibble, now 90 years old, lives simply in his home in North Salt Lake, where he and his wife, Audrey, have resided since 1947. A long gravel driveway heads straight towards an old garage with an old pickup truck and an equally old tractor, remnants of his farm life as a youth and the days when two acres of orchard were maintained (his peaches were legendary). Dibble walks with a cane, and his manner is measured and deliberate. But when he describes his work as a Mesoamerican scholar and specifically with The Florentine Codex, it is with a clarity, precision, and vividness that erase the intervening years.

The Place

Mesoamerica (literally, middle America) is a geographic designation

that does not correspond to our present-day map. It constitutes a cultural

region that extends roughly from north-central Mexico in the north to

parts of El Salvador and Guatemala in the south. Within this area were

societies that were every bit as complex and sophisticated as those in

Europe during the Precolumbian period. Besides being advanced in technical,

agricultural, scientific, and architectural realms, some societies had

social stratification and impressive urbanization. (For example, Tenochtitlan,

the capital of the Aztec Empire in central Mexico, had a population of

approximately 250,000, making it one of the largest cities in the world

at that time.)

|

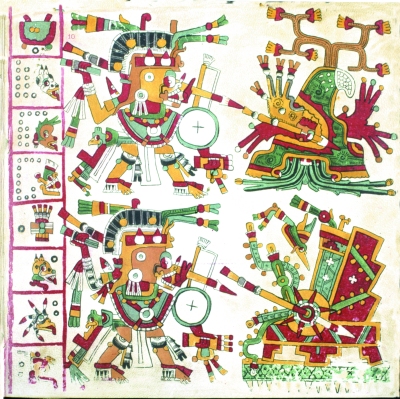

| Image from the Codex Cospianus, reproduced as a facsimile in 1898 from the original manuscript held in the library of the University of Bologna. |

One of the hallmarks of Mesoamerican

culture, which it shared with Europe but not the other native cultures

of the Americas, was a tradition of written record keeping. Mesoamerican

societies had writing systems and "books," known as codices.

A codex was generally painted on the bark of a fig tree or on deer hide

and was folded in an accordion style known as screenform. Instead of letters,

the codices conveyed information through beautifully painted glyphs. They

were used extensively to record everything from the history of a people

and dynastic genealogies to land and water rights, census lists, taxes,

and marriages.

A particularly interesting

aspect of codices was that the glyphs served as mnemonics, or devices

to jog the memory. They were intended to be the basis for an oral performance.

Additionally, only influential members of elite families were privileged

to learn this highly specialized form of knowledge, enabling them to "interpret"

the glyphs.

When Cortes arrived in 1519, the Aztec Empire was forever changed. Either through bloodshed or plague, the population was decimated. As part of the cultural conquest and subjugation of those remaining, Cortes and other Spaniards destroyed native Mesoamerican records. This determined effort was so effective that only 15 Precolumbian codices are extant today. Fortunately, our knowledge of the Aztec culture was preserved through a different source.

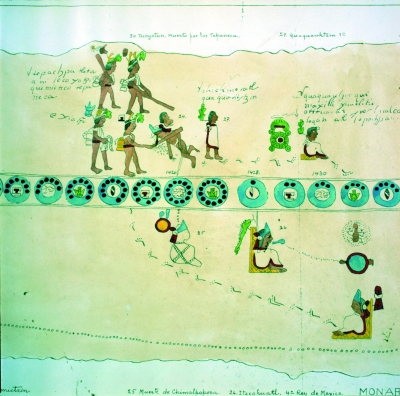

|

| Portion of Mapa de Tepechpan. The entire codex shows the chronology of events 1298-1596. |

The Codex

At the heels of Cortes came the next wave of conquerors, those who wished

to indoctrinate the natives into Christianity-the missionaries. Among

them was Bernardino de Sahagún, who, in 1529, was the 43rd friar

to arrive in New Spain. He easily became one of most accomplished in the

native language, Nahuatl.

Sahagún quickly recognized

that indoctrination of the natives might be more effective if the missionaries

had an understanding of the background, knowledge, institutions, beliefs,

environment, and practices of the Aztecs. As Dibble suggests, "If

you're going to control and convert a culture, you'd better understand

it first." To this end, Sahagún gathered Aztecs born and raised

prior to European contact and known to have extensive knowledge in specific

areas such as history, ceremonies and rituals, the physical environment,

legal and business transactions, and social interactions. All aboriginal

practices and beliefs were included, from scientific subjects such as

detailed descriptions of insects, medicinal plants, eclipses and constellations

of stars, to the minutiae of everyday life such as hairstyles, games,

tools, and even the piercing of the tongue.

First, artists and scribes

drew glyphs pertaining to the topic requested. Then an oral interpretation

of the glyphs was given, with Sahagún systematically questioning

the interpreter for greater clarity. The explanation was written, as Sahagún

had taught his students, in a phonetic transcription of the Nahuatl language.

The process took 10 years to complete.

The last phase was a singular

effort that involved methodically refining, revising, organizing, and

finally translating the entire text into Spanish. Sahagún created

what ultimately became a 12-volume encyclopedic monument to the Aztecs,

which he called The General History of the Things of New Spain.

This final edition included the glyphs, an abbreviated Spanish translation

in the left column, and the written phonetic transcription of the spoken

Nahuatl language in the right column. It took Sahagún almost 30

years, but he gave the world the very first ethnohistorical manuscript,

which to this day remains the longest text in a native language from anywhere

in the Americas and the most complete description of a native American

culture. It is also beautiful to behold, with vivid illustrations and

detailed ornamentation. It is a masterpiece of art and a monumental work

of scholarship. As Dibble says, "Sahagún rescued the knowledge

and the rituals of the Aztec civilization."

In about 1605, The General

History was sent to Pope Leo XI for his approval, and the codex ultimately

ended up in the Biblioteca Medicea-Laurenziana in Florence, Italy. Because

of this location, it has been referred to as The Florentine Codex.

For many years, it remained preserved, largely undisturbed and unexamined. It wasn't until the end of the 19th century that interest began to be rekindled, mostly in Europe. And then, in 1940, Sylvanus Morley, director of the School of American Research, provided the impetus that actually launched the translation of the codex into English.

The Translation

Morley knew of the expertise of Charles Dibble, who had completed his

doctorate translating the Codice en Cruz from the original Nahuatl

glyphs and was now teaching at the University of Utah. Morley found support

from President A. Ray Olpin. Dibble would teach part-time, and the University

would share equally the costs and benefits of publication with the School

of American Research in New Mexico. The complete project of translating,

editing, and publishing would be shared with colleague Arthur J. O. Anderson,

who was affiliated with the School of American Research. It was thought

that the endeavor would take five years.

Instead it took 30 years.

The two men, working from the original Nahuatl glyphs and text, completed

their translation in 1969, 400 years after Sahagún had finished

the Nahuatl version (1559-1569). "It was a labor of love," Dibble

says.

"Morley secured photographic

reproductions of The Florentine Codex, full size," Dibble

explains. "Anderson and I had duplicates. He and I worked on the

same section, I from Salt Lake, he from Santa Fe and then San Diego. We

both did the translations alone. Then we compared them and produced a

combined version. If we could not come to an agreement on the translation,

we would make a footnote explaining the variance."

Dibble, teaching for six months

each year, did some work on the project while teaching, but the bulk of

the translation was done during the six months of each year when he could

focus solely on this task. He and Anderson worked from the Nahuatl and

the glyphs-the Spanish was often abbreviated and sometimes not available.

They translated the 12 volumes in order of difficulty and size, leaving

the most difficult to the end. It was a project of scholarly challenge,

determination, and sustained commitment.

Mikkelsen, at one point, asked

Dibble if he would have done anything differently had he known it would

take 30 years. Dibble smiled and answered, "Well, fools rush in where

angels fear to tread."

The benefits of this venture have been tremendous. Within the international

community of Mesoamerican scholars, Dibble is renowned. He is considered

the best in the world in the scholarship and understanding of the natives

in Mesoamerica. He is credited with furthering the use of The Florentine

Codex as an essential resource, making it accessible to further study

and preserving the knowledge of the Aztec civilization.

It has also been a beneficial

collaboration with the University of Utah. The Marriott Library, as a

result of the interest in Dibble's work, has an impressive collection

of 53 facsimiles-reproductions so meticulously reproduced from the original

and so valuable that clean cotton gloves must be worn to handle them.

Included within this collection is one copy of The Florentine Codex.

Madelyn Garrett BA'82 MA'90, curator of the library's rare books division,

says, "Over the years, scholars have come from all over to study

the facsimiles. To have this extensive a collection in one location is

very valuable."

The collaboration with the University of Utah Press, first with Harold W. Bentley and later Norma Mikkelsen, both directors of the press, has also been beneficial to scholars and the University. Arthur Anderson wrote in his "Introductions and Indices" to The Florentine Codex, "They labored mightily with us….It is due to them that now for the first time, all the books of the Florentine Codex are in print and available." As Mikkelsen notes, "The Florentine Codex ...was the scholarly foundation of the reputation of the University of Utah Press."

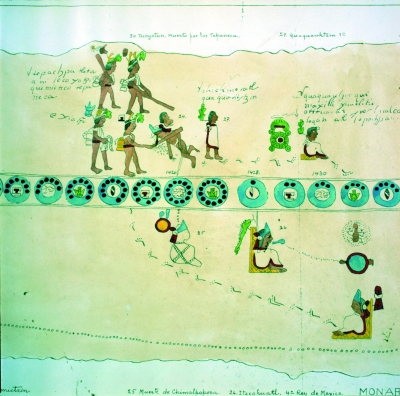

|

| Glyph from Vatican Library Manuscript #3773. Original codex is a continuous strip of 10 attached pieces of deerskin. |

Professor Dibble's legacy

continues at the University of Utah in terms of research and teaching.

The Department of Languages and Literature has been involved in the highly

specialized study of American indigenous languages. In the history department,

Rebecca Horn, an associate professor, works with graduate students on

the Nahuatl language and teaches undergraduate courses on Colonial Latin

America, including materials on Nahuatl and the history of Indian-language

writing and documents.

These are just a few of the

resultant ripples that were initially sent on their course by Charles

Dibble. Publicly, for his outstanding and far-reaching contributions,

Dibble was awarded the decoration and title Knight Commander, "Orden

de Isabel la Catolica," by the king of Spain, and the medal of the

highest honor from the Mexican government, with the title of Commander,

Order of the Aztec Eagle.

Although he is considered a national treasure in those countries, privately Dibble is modest and unassuming about his achievements. His accomplishments may merit a pilgrimage such as Werner Herzog's, but Dibble shies away from that sort of attention. He is a gentle man, one to whom a pilgrimage, he would say, is simply unwarranted.

I am tremendously indebted to Rebecca Horn, Associate Professor, Department of History,University of Utah, for her expertise and assistance in the preparation of this article.

-Elise Lazar is director of marketing for the Department of Theatre and a freelance writer.

Readers who would like to be in touch with Charles Dibble may send correspondence in care of Continuum, PO Box 591198, Salt Lake City, UT, 84158-1198.

Continuum Home Page - University of Utah Home Page - Alumni Association Home Page

Questions, Comments - Table of Contents

Copyright 2000 by The University of Utah Alumni Association