|

|

About Continuum Advertising Advisory Committee Archives Contact Us Continuum Home Faculty/Staff Subscribe related websites Alumni Association Marketing & Communications University of Utah Home |

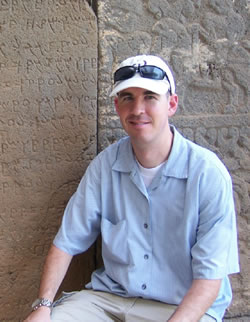

ALUM NOTE Turkish DelightSurviving Turkey, a soccer riot, and my first assignment in the Air Force JAG Corps.By Shane McCammon There is something oddly liberating about getting teargassed on a Friday afternoon. Maybe it’s the affirmation of life that comes with the first breath of clean air after just having thought that you would die in this Turkish soccer stadium—a painful death caused by the swirling yellowish smoke that makes your eyes burn blind and shreds your lungs with what feel like acid-soaked wire bristles. Or maybe it’s the intoxicating thought that, now that you’ve been teargassed on a Friday, what could the rest of the weekend possibly bring? Whatever the reason, my two friends and I found ourselves laughing deliriously as we sped home through the pitch-black Turkish countryside, passing buses full of swollen-faced soccer fans headed back to the industrial cities that dot the Mediterranean here. We had taken the day off and driven four hours each way to watch our beloved Turkish soccer team’s final match of the season. On the line: Turkish pride, a spot in Turkey’s prestigious Second League for the next year, and, apparently, our lives. In the waning seconds of the match, our team gave up the winning goal, thereby kicking off a series of events that saw our fellow fans rain debris—stadium seats, metal poles, burning flares—on the police, stampede toward the pitch, and rip apart a responding fire truck piece by piece. As often happens in the developing world, the local police responded with tear gas and billy clubs. Swallowed by the crush of sweaty bodies trying to reach the field, we had nowhere to run or hide. And surprisingly, burying my face in my $10 polyester replica jersey did nothing to stop the gas. The riot reaffirmed several lessons: First, Turks are a passionate people. They care deeply about their soccer teams, their families, and (maybe above all else) their culture and their place in the world. After all, this is a country where insulting a Turk is a federal crime. Second, when attending a Turkish soccer match, it’s always good to stay away from the hooligans. However, when you and 12,000 fellow fans go to the trouble to get off work, pay $12 a gallon for gas, and travel four-plus hours for a 90-minute game, only to turn right back around and drive home that night, everyone is a hooligan. Including you.  Shane and his wife, Emily, in 2007, when Shane was named Company Grade Officer of the Year for Turkey. And finally, it’s great to be an American. In the midst of the riot, my friends and I inexplicably found ourselves on the lush playing field, coughing, gagging, and blindly wandering past club-swinging police. The fire truck was being dismantled not more than 20 feet away from us. A line of riot police wielding plastic shields and batons blocked our path out of the stadium. Ignoring any pretense that we were blending in with the locals, I approached the friendliest-looking officer and explained in Turkish-English Creole that we were Americans, that we renounced our own soccer team, and that we would very much like to leave the stadium and live to see our beautiful wives and children. After staring at us as if we had just told him we were from Neptune and would like to meet his leader, he stepped aside and let us pass to safety. There have been very few times when I’ve been as happy to be an American. One other such time was when I graduated from Commissioned Officer Training (COT) in 2006. Maybe it’s corny, and maybe it’s time to cue the patriotic music, but as I stood on the parade grounds with 68 fellow officers, I truly felt like I was part of something great, something bigger than me. While I could make more money as a lawyer in the civilian world, I realized on COT graduation day that my fellow law school classmates likely did not have the same pride in their firm as I had in mine. Yes, I was joining the military at a time when our nation was fighting a war under perhaps dubious circumstances, but I was part of an Air Force Judge Advocate General’s Corps that relishes its independence and has fought for the Rule of Law—both in foreign countries and, sadly, in ours. I was joining a family that had turned out in force for a funeral I attended in 2004 for a friend’s brother, who was killed in Iraq. I was (and still am) proud to serve my client—something many lawyers can’t say. One thing I never thought I would say is “Yes, sir” when asked if I was serious about joining the military. When I was at the University of Utah—studying English and working at The Daily Utah Chronicle—I figured the closest I would ever get to the military would be as a war correspondent. After all, I didn’t exactly take to authority, a fact that was not lost on the University administrators with whom I worked as editor-in-chief of the Chronicle. But after graduation, I found myself thinking there had to be more to life than passively writing about people’s problems, hoping others would be inspired to take action. So, naturally, I decided to go to law school. But because the idea of logging 80-hour weeks for a law firm made my stomach churn, I looked for public-sector opportunities that would allow me to get inside a courtroom and still pay enough to feed my three children. So there I was, on the parade grounds, marching in formation past a one-star general, trying my best not to trip over myself. From COT, my family and I left for Incirlik Air Base, just outside of Adana, Turkey. Located in a sweltering cotton- and citrus-growing region approximately 20 miles from the Mediterranean and 70 miles from the Syrian border, Incirlik processes roughly 75 percent of the materiel headed for Iraq and Afghanistan. During morning runs around base, my iPod is inevitably drowned out by low-flying behemoths carrying supplies “down range,” and my children have learned to sleep through the seemingly constant whir of jet engines and the occasional test-firing of anti-aircraft artillery. Due to security concerns since the 2003 invasion of Iraq, all U.S. personnel and their families are required to live on base. As a result, we reside in a Middle Eastern version of Mayberry, where everybody knows your name (and business), and where you can’t go to the on-base grocery store or the gym without bumping into a dozen acquaintances. Above all, it’s a tight-knit community where kids roam freely through family housing, riding their bikes and climbing on playgrounds as the call to prayer blasts from the minarets of off-base mosques. I began my JAG career by advising commanders on myriad civil law issues—everything from claims against the government and Freedom of Information Act requests to international and operational law issues. And despite not knowing anything about taxes or how to balance my own checking account, I was put in charge of running our base’s version of H&R Block.  The McCammon family I have since moved on to other trials and bigger responsibilities. In July 2008, I was assigned as the only military defense attorney in Turkey. My clients are scattered throughout Europe and the Middle East—stretching from the Azores in the middle of the Atlantic all the way to Kyrgyzstan in Central Asia. Approximately half of my clients are in Iraq and Afghanistan, where they try to balance the stress of fighting a war and being away from loved ones with the anxiety that comes from being under investigation for accidental weapon discharges, sleeping on duty, and abusing prescription drugs. I have defended airmen accused of terrible crimes and have seen and heard things I wish I could delete from my memory. But I will never forget the time a client’s mother tearfully hugged me and my co-counsel after the unfounded rape charges against her son were dropped on the eve of trial. And while my experience is a far cry from the JAG television show—to date, I have not been issued my own fighter jet or been asked to negotiate with the Iranians—I wouldn’t trade it for any other. I wouldn’t trade spending Saturday afternoons retracing the footsteps of Alexander the Great, St. Paul, and the Crusaders; or a Sunday morning standing in the glow of sun-lit mosaics inside the Hagia Sophia; or the countless hours sipping apple tea in carpet shops. I wouldn’t trade having the opportunity to talk with my son about how fortunate we are as we drive through a muddy, ramshackle Turkish village, trying our best to avoid the roaming goats and chickens on our way to a cliff-top castle once ruled by Armenian kings. I wouldn’t even trade getting teargassed on a Friday afternoon. – Shane McCammon BA’03 is an Area Defense Counsel in the U.S. Air Force JAG Corps. |