|

|

About Continuum Advertising Advisory Committee Archives Contact Us Continuum Home Faculty/Staff Subscribe related websites Alumni Association Marketing & Communications University of Utah Home |

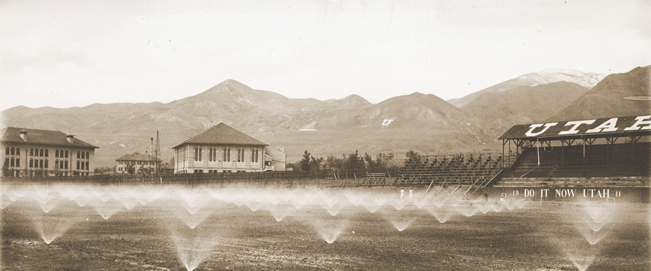

Sidelines Sprinklers watering Cummings Field in 1911. Historical photos courtesy Special Collections, Marriott Library, The University of Utah

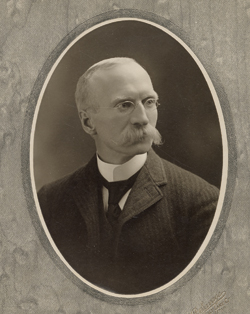

By Parry D. Sorensen  Professor Byron Cummings, who arrived at the U from Rutgers University in 1893.

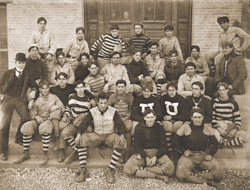

There aren’t very many of us still alive who ever saw a football game on Cummings Field, which served as the University of Utah’s football stadium for a quarter of a century. It was located north of Rice-Eccles Stadium, where the chemistry building and Einar Nielsen Fieldhouse now stand. The board of Regents named the field in grateful recognition of the efforts of a young professor of Greek and Latin—Byron Cummings—who arrived at the U from Rutgers University in 1893. Within a year he had organized a group to raise funds for U of U athletics. In 1897 he even coached the football team to an undistinguished 1-6 record. After that, he put all his efforts into raising money and teaching his classes. Before moving to “the hill” (its present location) in 1900, the University of Utah campus was located on the current site of Salt Lake City’s West High School. Games were played on a field near 900 South and Main. Since there were no stands, spectators were scattered around the sidelines. Cummings moved among the audience, soliciting funds to support the team. According to Prof. Walter A. Kerr, who wrote a history of Utah athletics, “Byron Cummings believed that athletics were an important part of our culture, not a luxury. He considered development of one’s body vital to the development of a person’s intellect.” When the campus moved up the hill at the turn of the 20th century, Cummings and two other faculty members surveyed the site and picked out the spot for the football field. He then organized a group, mostly of students, who cleared the sagebrush and hauled in loads of sand and soil. Before moving to “the hill” (its present location) in 1900, the University of Utah campus was located on the current site of Salt Lake City’s West High School. Games were played on a field near 900 South and Main. Since there were no stands, spectators were scattered around the sidelines. Cummings moved among the audience, soliciting funds to support the team. From then on, Cummings had a hand in all the future development of the field. He directed a group of engineering students in surveying and installing a sprinkling system, and led another project involving layout of a quarter-mile track around the field. He recruited faculty members to serve as timers and judges at track and field events, and would even sometimes shorten class periods so that students could help workers on projects like installing a high board fence to make sure everyone paid for their entry into a game. The growing popularity of football meant adding more seats every year until by 1910 the red-painted wooden stands could hold 5,000 spectators.  The University of Utah football team circa the early 1900s.

Cummings’ efforts on behalf of athletics didn’t interfere with his academic life. On the contrary, he became dean of the School of Arts and Sciences and was acting dean of the medical program for two years. In civic affairs, he was elected to the Salt Lake City Board of Education. He spent summers in Southern Utah and Northern Arizona collecting artifacts, eventually being recognized as an anthropologist in addition to a professor of languages. In 1915, after 23 years on the U of U faculty, Cummings left for a prestigious professorship at the University of Arizona, and later became president there. Besides varsity football and intercollegiate track and field meetings, Cummings Field was used for outdoor physical education classes. Several East High School games were played there every season, and it was for many years the permanent site of the state high school track and field meets. There were no dressing rooms, so teams had to use the U’s gym about 75 yards away. The last game played on Cummings Field was the traditional Utah-Aggie game on Thanksgiving, 1926. Both teams were undefeated, and the championship of the Rocky Mountain Conference was at stake. Tension was high. To meet the demand for tickets, three rows of folding chairs were placed on the track, and bleachers were added to each end zone. The Utes won 34 to 0. That convinced everyone that Utah needed a bigger stadium. Thanks to the combined efforts of town and gown, the Utes opened the 1927 season in their new 20,000-seat stadium. Over the following 75 years, there were numerous additions and improvements, including 10,000 seats at the north end, where commencements were held and summer entertainment events were presented. The cost to build the stadium in 1927 was $155,000. The price tag for expanding Rice-Eccles Stadium in 2002 was $55 million. Return to Winter 2008-09 table of contents | Back to top Heavenly Days

|

||||