Bookshelf

Healing A Heart

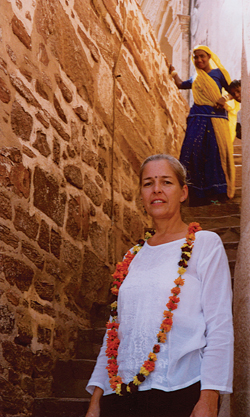

For Maggi Grace, what began as a journey to save a loved one’s life turned into a life-altering experience.

By Linda Marion

Photo by Jackie Helvey

Consider this scenario: Your companion, whom you care about deeply, is suddenly diagnosed with a life-threatening condition that demands immediate medical attention. Your partner is in his early 50s, self employed, physically active, and has been in excellent health all his life. He does not carry health insurance. You are told at the local hospital that the surgery required to save his life will cost more than $200,000, but neither of you has any substantial savings or access to other resources. What do you do?

This is the situation in which U of U alumna Maggi Grace BA’85—a writer, teacher, and artist who lives in North Carolina—found herself in 2004. She and her partner, Howard, had been together for almost a year when a routine physical examination revealed that he had a leaking mitral heart valve and needed an operation immediately; otherwise, he could die at any moment.

For both, it was a bolt from the blue, and neither had a clue as to what to do.

A similar scenario could unfold for the estimated 46 to 50 million uninsured Americans who are at risk for bankruptcy, or worse, if confronted with a major medical crisis. Health care in the U.S. has become a central issue in the upcoming presidential election—one that raises moral, as well as financial, concerns. How, it is often asked, can the richest country in the world allow people to be denied health care because they can’t ‘afford’ it?—a question that loomed large in Maggi’s mind as she and Howard began searching for a solution.

They first attempted to persuade the local hospital to lower its costs to the amount an insurance company would reimburse for the surgery and care, but they were turned down flat. They searched for other hospitals around the country that might charge less, but to no avail. And getting health insurance was out of the question because of Howard’s now “pre-existing condition.” Alternatives were rapidly dwindling when Maggi’s eldest son, Bryan, then a medical student at Stanford who had spent time in India, suggested they go there for the operation, where it would be much cheaper while still of the highest quality.

After receiving assurances from various sources, not the least of which was a personal phone call from the highly recommended cardiothoracic surgeon who had founded Escorts Heart Institute and Research Center, the facility they were looking into, Maggi and Howard headed for New Delhi in September 2004. Howard ultimately underwent two surgeries at the institute—one to repair the heart valve and, when the repaired valve developed a thickening of the septum, blocking blood flow, a second to replace the valve—at a total cost of less than $10,000, including round-trip airfare, surgical costs, three weeks in the hospital, and extensive post-operative care.

Maggi was a constant and concerned companion during the ordeal, taking care of details and spending many hours at Howard’s bedside, monitoring his progress. She admits that it wasn’t easy adapting quickly to different cultural mores and habits, but she was impressed with the efficiency and professionalism of the doctors and the hospital staff. Even so, she observes, “There’s no way to be in India and not see the poverty—people living under tarps next to a state-of-the-art hospital.” Over the next few weeks, she grew to love the country and the people she met there. (She has since returned to India five times. Her sojourns there, she says, are “something like coming home: the sights, smells, sounds — everything about it. If I ever get used to it, I’ll be disappointed.”)

During that first trip to India, Maggi also became aware that what had begun as a journey to save a life was evolving into a journey of intense self-discovery.

Maggi had set up a Web site (http://howardsheart.com/) and began posting updates to keep family and friends aware of Howard’s condition. And as is her habit, she maintained a personal diary to record her experiences, drawing mandalas “to do something” with all she was feeling and learning.

When the couple returned to the U.S. in October 2004, the interest level in “medical tourism” was in crescendo. The Web site had attracted much interest, and a mountain of e-mails—from heart patients, reporters, legislators, students, bloggers—was waiting to be answered. “It was overwhelming,” says Maggi, who spent days and nights writing responses.

The worldwide media had caught wind that Maggi and Howard had been the first medical tourists to choose to receive critical surgery in India, and journalists from CNN, Bloomberg Magazine, The Washington Post, and ultimately, 60 Minutes, 20/20, and the AARP were among those who began contacting them. Maggi and Howard were interviewed repeatedly, and stories of their experience blossomed in newspapers and Internet sites across the country. They were even asked to testify before a U.S. congressional committee looking for solutions to the health care crisis. “Because of all the media coverage,” she explains, “I realize I have been a patient advocate ever since returning from India that first time.”

She has also become a published author. Her journal came to serve as the basis for State of the Heart: A Medical Tourist’s True Story of Lifesaving Surgery in India (New Harbinger Press, August 2007; http://maggigrace.com/stateoftheheart/). Usually it takes a long time to get a book published, especially for a first-time author, but there was so much interest in the topic that Maggi’s book was snatched up quickly, with very few changes made. And while she hadn’t set out to write a book—“not at all,” she says—it became clear that it was the best and most efficient way of responding to the numerous inquiries coming her way.

As for Maggi and Howard’s personal relationship, the experience that could have brought the couple closer together eventually did just the opposite: The stresses and strains of the ordeal threw Howard and Maggi into what she describes as “a much more intense relationship—something that you might expect to have later in life, not one that couples usually navigate in the first year of dating.”

In 2006, Maggi and Howard separated.

“It was extremely complicated for me,” says Maggi. “I speak about him almost daily now because of the book”—at events including author appearances, readings, and other occasions, most recently at a global conference on health care in Las Vegas, followed by a forum on the ethics of medical tourism at Harvard Medical School—“but I haven’t seen him for over two years.”

“I don’t know exactly what happened,” she says. “But so many issues came up when writing the book—things like how to take care of someone you love and still allow them some level of the independence they are used to; how to take care of ourselves while taking care of someone else—that it’s no surprise the experience took its toll.”

In spite of her distress over the separation, Maggi has been touring the country to promote the book and make people aware of the advantages of medical tourism as well as the growing health care crisis in the U.S. “Our health care system is broken,” she says. “Everyone knows that. I’m not a policymaker or economist, but as long as we have pharmaceutical and insurance companies making decisions for medical professionals, there’s a problem. We need to start over with a new model.”

Maggi hastens to add that she isn’t “against U.S. doctors and nurses.” On the contrary, she explains, “they do a superb job, but we have given them a tiny box to run around in. They are controlled by people who have their own bottom line as their priority, not the patients’ well-being. The doctors and nurses in my audiences are as upset as we are with the situation.”

In the meantime, medical tourism is growing exponentially. “An estimated 150 million people worldwide are now traveling to other countries for health care treatment. It’s become a $32 billion industry,” she says, “depending on whom you ask.”

All of these experiences—traveling to India, observing another culture, separating from Howard, talking and writing about health care—have combined to heighten Maggi’s awareness of the wider world and her role in it. In December of 2006, she traveled to India to spend Christmas with her children and ended up volunteering in a facility for children orphaned by the 2004 tsunami. In spring of 2008, she spent three weeks traveling around Laos with her son Bryan. “It’s such a life-changing experience to visit a developing country,” she says. “We [in the U.S.] take everything for granted. We don’t need all these ‘things’ we have. There are millions of people in the world who live so simply, with very little, yet seem so happy. We’ve lost touch with the unmaterialistic world, with the Earth.”

As for the future, Maggi is interested in addressing other cultural issues, such as caring for the elderly—perhaps in a book, when she can find some quiet time.

In the meantime, she has made herself available as a Patient Advocate to those considering going overseas for medical treatment, and even as a Patient Companion for those who cannot take their spouse or other family member with them. “No one should go alone,” she says. “Patients need someone to navigate the system for them, to be a liaison to the hospital staff.”

Maggi also continues to accept invitations to speak to a wide variety of audiences about her experience, drawing attention to health care and other issues of concern—for the planet and the people who occupy it. “I’d never felt like a globally thinking person until I traveled to India,” she says.

And that has made all the difference.

— Linda Marion BFA’67 MFA’71 is managing editor of Continuum.

EXCLUSIVE TO THE WEB:

|